VC&G Interview: Jerry Lawson, Black Video Game Pioneer

February 24th, 2009 by Benj Edwards In late 2006, I received a large collection of vintage computer magazines from a friend. For days I sat on my office floor and thumbed through nearly every issue, finding page after page of priceless historical information. One day, while rapidly flipping through a 1983 issue of Popular Computing, I encountered a photo that stopped me dead in my tracks.

In late 2006, I received a large collection of vintage computer magazines from a friend. For days I sat on my office floor and thumbed through nearly every issue, finding page after page of priceless historical information. One day, while rapidly flipping through a 1983 issue of Popular Computing, I encountered a photo that stopped me dead in my tracks.

There I discovered, among a story on a new computer business, a picture of a black man. It might seem crazy, but after reading through hundreds of issues of dozens of publications spanning four decades, it was the first time I had ever seen a photograph of a black professional in a computer magazine. Frankly, it shocked me — not because a black man was there, but because I had never noticed his absence.

That discovery sent my mind spinning with questions, chiefly among them: Why are there so few African-Americans in the electronics industry? Honestly, I didn’t know any black engineers or scientists to ask. I tried to track down the man in the magazine, but all my leads ended up nowhere. I’d have to put the matter aside and wait for another opportunity to address the issue.

Fast forward a few months later, and I’m standing on the showroom floor of Vintage Computer Festival 9.0. As I spend a few minutes thumbing through a vendor’s large array of cartridges for sale, I hear a voice from behind.

“Do you have any Videosoft cartridges? Color Bar Generator?”

I turn around and notice a large black man in a wheelchair, hair graying at the edges. He seems out of place. I scan the crowd — yep, he’s the only black guy here. Fascinating — what’s his story? Instead of bumbling through a few impromptu questions and making a fool out of myself, I decide to research his identity first.

As it turns out, the man I encountered that day was Gerald A. Lawson (aka Jerry), co-creator of the world’s first cartridge-based video game system, the Fairchild Channel F. Naturally, he was attending VCF 9 to give a presentation called, “The Story of the Fairchild Channel F Video Game System.”

Jerry Lawson (L) discusses Fairchild Channel F schematics at VCF 9.0.

Jerry Lawson (L) discusses Fairchild Channel F schematics at VCF 9.0.

Being one of only two black men (I know of) deeply involved in the industry’s earliest days, Jerry Lawson is a standout figure in video game and computer history. He’s a self-taught electronics genius who, with incredible talents, audacity, and strong guidance from his parents, managed to end up at the top of his profession despite the cultural tides flowing against him.

Growing up in America, a land of endless diversity, we tend to fall into certain cultural grooves — well-defined paths of cultural history — that both unite and separate us. We get comfortable with those grooves and use them as the basis of our assumptions about behavior within certain age groups, socioeconomic classes, and ethnicities. Despite this ingrained cultural momentum, there are still people who manage to skip those grooves and chart their own course, ignoring any conventions that get in their way. Jerry Lawson is one of them, and he’s got an important story to tell.

This interview took place on February 6th, 2009 over the telephone.

[Update (04/11/2011): Jerry Lawson passed away on April 9, 2011 at the age of 70.]

[Update (2015): Read my in-depth account of the creation of the Fairchild Channel F and the invention of the video game cartridge at FastCompany.]

[Update (2017): If you enjoy this interview, check out my interview with Ed Smith, another early black video game pioneer.]

Early Life

Benj Edwards: For history’s sake, when and where were you born?

Benj Edwards: For history’s sake, when and where were you born?

Jerry Lawson: December 1940. I grew up in Queens, New York City.

BE: How did you get into electronics?

JL: I started very young. I went to school, but I was an amateur radio guy when I was thirteen. I was always a science guy since I was a little kid.

BE: Do you have a family history in engineering?

JL: I found out only later in life that my grandfather was a physicist. Because he was black, the only place he could work was the post office. He was a postmaster. He went to some school in the south — I don’t know which one it was.

BE: Did your father do anything like that too?

JL: My father was a brilliant man, but he was a longshoreman. He could work three days a week on the docks and make as much money as most people did in six days. He was a science bug — he used to read everything about science.

BE: He probably encouraged you to do experimenting when you were a kid.

JL: Yeah, he did. In fact, some of the toys I had as a child were quite unusual. Kids in the neighborhood would come see my toys, because my dad would spend a lot of time giving me something, like the Irish Mail. The Irish Mail was a hand car that operated on the ground. It was all metal, and you could sit on it. You steered it with your feet, and it had a bar in the front, and the bar with a handle. You’d crank it, and it would give you forward or backward motivation, depending on which way you start with it.

I was probably the only kid in the neighborhood who knew how to operate it, so I used to leave it out all night sometimes. I’d find it down the block, but no one would take it, because they didn’t know how to operate it.

BE: So that must have been in the 1940s then.

JL: It was in the ’40s, yep. I also had an amateur radio station in the housing project in Jamaica, New York. What happened was, I tried to get my license, and the management wouldn’t sign for it. And it was really hard for me as a kid to research literature and the public things I could find, but I found that it said if you lived in a federal housing project, you didn’t need their permission. Hot diggity! So I got my license, passed the test, and I built a station in my room. I had an antenna hanging out the window.

I also made walkie-talkies; I used to sell those. I did a bunch of things as a kid. My first love started out as chemistry, and then I ended up switching over to electronics, and I continued on and even got a first class commercial license — in fact, I worked a little while in a radio station as chief engineer.

BE: Did you attend college?

JL: Yes, I did. I went to Queens College, and I also went to CCNY.

BE: Did you study electronics there?

JL: Before I had studied electronics, I had pretty much been into electronics all the way around. When I was 16 or 17 years old, I used to repair TVs at different shops I would go to. I did what they called “dealership work.” And I used to also fix TVs by making house calls. It was a place that had opened up in Jamaica, New York that was called Lafayette Radio. And I used to spend almost every Saturday at Lafayette Radio. Lafayette Radio was a huge electronics store. They had tube testers, capacitors, resistors — you name it, they had it. And my mother used to give me a small allowance, and I’d go down and buy parts.

There were two other electronics stores — one was called Peerless, and the other was called Norman Radio. My budget would say, well, I could only afford a capacitor this week, so I’d buy a capacitor. I could only afford a socket, and I’d save my money up for a socket. How ’bout a tube? And I ended up building my transmitter from scratch.

First Computer Encounters

BE: What was the first computer you ever used?

JL: The first computer I ever used was known as the [Forest?] 65L. It was the world’s first militarized, solid-state computer. It was designed by ITT, and I went to a training school for it. Built inside a mountain. They were like the push-button war machines you see in the movies. Remember the movie Fail-Safe? That was that machine.

BE: What brought you to see that computer?

BE: What brought you to see that computer?

JL: I was working for Federal Electric — ITT. Federal Electric was their division of field sales people that went around different parts of the world and did developments and projects. I was hired by them originally to go to Newfoundland to put a radar set back online — to finish the installation and adapt the modifications so it could be put online and used. My first love was imagery and radar. Computers were simple stuff.

BE: To fast forward a little bit, before I get off your history with computers, do you remember the first personal computer you ever used in the 1970s?

JL: Two of them — that is funny, because I had an Altair. And before that, I also had — Fairchild gave me a DEC PDP-8. I put the PDP-8 back into work. In fact, the PDP-8 is a story in itself — that ended up running a school in my garage. With the PDP-8, I had two tape units, the tape controller, a high speed tape reader, and all the maintenance boards and backup spares for it. My garage became a service depot.

DEC said I had the only operating PDP-8 — straight 8 — west of the Mississippi. And they asked me if they could run classes in my garage on it. As a result — my PDP-8 had a control unit on it called the TC01. And the TC01 didn’t have all the maintenance updates on it. They said it would cost about ten grand to update it, and I said, “Well heck, I’m not paying ten grand.” So they said — for them having the class in my garage with the guys there — they would do the updates for free. They did. The whole updates for free.

My neighbor came over one day, and the funniest part of it was he walked in, and — it was not just the computer, it was the computer and all the stuff that went with it. The unit itself was about, oh, eight feet by six feet, and about three feet deep. And it sat in my garage, and I even ran a special power line to it. And he walked in one day and he saw it running, and it was running what we called the exercise routine, which was a maintenance routine I used to run on it. And he saw these tape reels running back and forth, and lights going on and off, and he looked at me and he said, “Is that what I think it is?” I said, “What do you think it is?” He said, “Is that a computer?”

My neighbor came over one day, and the funniest part of it was he walked in, and — it was not just the computer, it was the computer and all the stuff that went with it. The unit itself was about, oh, eight feet by six feet, and about three feet deep. And it sat in my garage, and I even ran a special power line to it. And he walked in one day and he saw it running, and it was running what we called the exercise routine, which was a maintenance routine I used to run on it. And he saw these tape reels running back and forth, and lights going on and off, and he looked at me and he said, “Is that what I think it is?” I said, “What do you think it is?” He said, “Is that a computer?”

“Yeah.”

And he said, “You got a computer in your garage?”

“Yeah.”

“Did you get one when you bought the house?” [laughs]

BE: What year was that?

JL: That was ’72, I think — ’70 or ’72, around in there.

BE: That’s really early for having a computer in your garage.

JL: I had an ASR-33 teletype machine too. That was the output for it — printer input and output. And my daughter used to love to come in run this one little thing — she knew how to hook the speaker next to the data line, and it played a song. She would go load that in — and she new how to load it — so it would play that song.

JL: I had an ASR-33 teletype machine too. That was the output for it — printer input and output. And my daughter used to love to come in run this one little thing — she knew how to hook the speaker next to the data line, and it played a song. She would go load that in — and she new how to load it — so it would play that song.

BE: Did you play any games on it?

JL: Lunar Lander. It was all text, no graphics.

Early Electronics Career

BE: Take me through your early electronics career. Besides ITT, where else did you work before Fairchild?

JL: I worked for Grumman Aircraft, Federal Electric, and PRD Electronics.

PRD Electronics was the job I went to when I left New York. That was a computerized test facility called [VAS], and we used the 1218 UNIVAC Computer. I went to programming school for the 1218, and we wrote software for it, and we all wrote a part of it which was a compiler that we called VTRAN.

I used to hate programming. It was a drudgery I really hated to do. We had two methods of writing programs: one was what we called “ELP,” an English language program, then we had to convert it to a thing called VTRAN, which was our own language we developed.

I worked for PRD about 4-5 years, I guess, and I transferred to a company called Kaiser Electronics, which was out in Palo Alto.

BE: When you were working for Grumman and those places, was that on the East Coast, or had you already gone to California?

JL: On the East Coast. When I went to Kaiser, that was the first time I went west.

BE: What what was Kaiser’s main business?

JL: Kaiser was doing military electronics — particularly the displays. They did the head’s up display (HUD) for the A-6A Grumman aircraft. They also did the VDI, which was the vertical display indicator. The HUD was a system that shined on the pilot’s canopy so you wouldn’t have to watch the turn-bank indicator, speed, what have you. The vertical display indicator was something that was on the dash, which was a scope tube, like a TV image, that let you see — for instance, if you had plotted a course, whether you were turning away from that course, whether you were on course, whether you were flying upside down. Little goodies. What the ground texture was. The HUD would just show you instruments. The VDI would show you the ground return — in other words, if it was jungle you were flying over, or mountains.

After Kaiser, I kicked around the semiconductor industry for a while. I was in between marketing, and I was also in engineering applications.

BE: How were the job prospects for a black engineer in those days? Did your race affect that in any way?

JL: Oh yeah, it always did. It could be both a plus and a minus. Where it could be a plus is that, in some regard, you got a lot of, shall we say, eyes watching you. And as a result, if you did good, you did twice as good, ’cause you got instant notoriety about it.

Consumer Electronics and Fairchild

BE: Do you think that people in the aerospace industry and military defense had a lot of influence in computer development? Was there any cross-pollination between folks like you who went from working on military electronics to consumer products?

JL: Yeah, because what happened was we got to use technologies that were not, shall we say, consumer-type stuff. But yet, we were on the leading edge of pushing the state of the art so that things would become more practical. For example: there was no [DB-9] connector for high volume use in computers. The DB-9 connector originally cost an arm and a leg. But when the computer and consumer industries came along, it became plastic, it became higher volume, and it became a reality to use. Before then, it was used in military all the time. That was a cross-over kind of a thing.

JL: Yeah, because what happened was we got to use technologies that were not, shall we say, consumer-type stuff. But yet, we were on the leading edge of pushing the state of the art so that things would become more practical. For example: there was no [DB-9] connector for high volume use in computers. The DB-9 connector originally cost an arm and a leg. But when the computer and consumer industries came along, it became plastic, it became higher volume, and it became a reality to use. Before then, it was used in military all the time. That was a cross-over kind of a thing.

The semiconductor content got cheaper and cheaper because of volume. The military components were not that high volume, but they were very stressful, they were high-reliability parts. But however, you take that same part and use it over and over again in a consumer product — you know, one of the things I used to always say, I said, “Military was good training for consumer, because consumer products actually have to be stronger than military.” Everybody said, “Get out of here!” I said, “Nah. Just think about it for a second.” I said, “If I did a military product, I can train the individual how to use it. If he decides to tamper, destroy, or mal-use it, I can bring him up to charges, can’t I? I can insist that he reads, that he’s trained in how to turn and turn it off, right?” They said, “Yeah.” “Try that with a consumer.”

BE: Instead they hit it with a hammer and dunk it in the toilet, right?

JL: Yeah, I’ll tell you what happened. The first year we put out the Fairchild video game, I made the mistake of going to work the day after Christmas. The day after Christmas in the consumer business is called “Hell day.” Why it’s called “Hell day” is because that is when everything comes back to the store, and the person couldn’t use it.

JL: Yeah, I’ll tell you what happened. The first year we put out the Fairchild video game, I made the mistake of going to work the day after Christmas. The day after Christmas in the consumer business is called “Hell day.” Why it’s called “Hell day” is because that is when everything comes back to the store, and the person couldn’t use it.

So I start getting calls — there’s nobody in the factory except the guard and me. I’m there in the plant to take care of some paperwork. He starts transferring calls to me. They had one guy call me, and he wanted to know where the batteries go. I said, “There is no batteries.” He took the thing apart looking for a battery in there!

One guy called up and said, “Dog urine hurt the game.” The dog lifted his leg and peed on it!

And one of the things that really cracked me up is that I was starting to get really jaded by answering the phone, right? One woman called up, really irate, and she said, “My game hums! Do you know why?” And I said, “‘Cause it doesn’t know the words, lady.”

BE: Good answer.

JL: And even the guard said, “All right, Jerry, I won’t give you any more calls.” I said, “That’s a good idea.” [laughs]

BE: That’s a great story. So how did you end up at Fairchild?

JL: Fairchild was gonna start this brand new thing called freelance engineering. They wanted somebody to be able to go around and help customers with designs. I was available, and they knew I was an apps guy. They gave me two opportunities. They said, “You could either go inside in our linear department and work there in marketing, or you can go in the field. If you go in the field, it’s a brand new deal; you’re the first guy.” And I said, “Yeah, I’ll take that.”

When I was there for the first six months, I said, “You know, there’s a problem here. The problem is that Fairchild is not known for being helpful for customers. And I’ve got an image to overcome: how the heck to break down that image they have.”

Me and a sales guy got together, and I wrote a proposal called “Take Fairchild to the Customer.” And the heart of that proposal was a 28-foot van — mobile home. And I wanted to tear it down and put in product demos, literature — a laboratory on wheels. They went for it. I went to a company called Formetrix, and they built the inside of it, and it looked like something from James Bond. It even had a rear-projection screen that came out of the ceiling. It turned out to be an overwhelming success, so they came back to me and said, “We want you to do it again.”

Me and a sales guy got together, and I wrote a proposal called “Take Fairchild to the Customer.” And the heart of that proposal was a 28-foot van — mobile home. And I wanted to tear it down and put in product demos, literature — a laboratory on wheels. They went for it. I went to a company called Formetrix, and they built the inside of it, and it looked like something from James Bond. It even had a rear-projection screen that came out of the ceiling. It turned out to be an overwhelming success, so they came back to me and said, “We want you to do it again.”

So I went to FMC, and they had a brand new coach they built. The rear-end was the Bradley differential for a tank. It had a 485 cubic inch engine, a 50-gallon gas tank, four air condition units, and it drove like a car. The wheels were in tandem, next to each other. That thing was somethin’ else.

One time, my daughter wanted to ride in it. I said, “Oh, ok.” So I got her in it. The guys at FMC said they had just tried out a brand new cruise control for it. I said, “Oh that’s nice.” They said, “Let us know how you like it.”

I got out on the highway and pushed the cruise control; it took over. I went to disengage, and it wouldn’t disengage. And I went, “Oh my god.” I slammed on the brakes, and it was riding the brakes. I came around, and there was a truck and some cars parked at a light, and I was trying to figure out which one of these vehicles I’m going to rear end, right? Just then, I reached down and pulled all the wiring out. It cut the engine off.

I brought it back in a slow walk and said, “You clowns.” And I told them what happened and they said, “Oh my God, it didn’t disengage?” I said, “No.”

There at the Beginning — Atari and Apple

BE: What year did you start working at Fairchild?

JL: 1970, I think.

BE: What were Fairchild’s main products at the time?

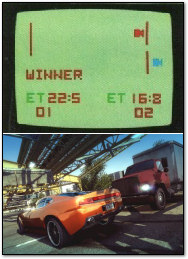

JL: Oh, they had everything: memories, linear devices. They had LED devices. They were a full-line semiconductor place. They even had a microprocessor they brought out called the F8, which is the one I incorporated into the game. Two kinds of games: I made a game in my garage called Demolition Derby in oh, ’73? ’72?

BE: When you did that, had you seen Pong or any other games?

BE: When you did that, had you seen Pong or any other games?

JL: When they started to work on Pong, there was a gentleman — I went in to see him one time, and he worked at a company called “Syzygy.” The guy’s name was Alan Alcorn. The name of the two other guys were Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney. It was the beginning of Atari.

BE: Did you know those guys?

JL: Yep, very well.

BE: Did you help them with any projects?

JL: Not really — I tried to sell Alan a character generator. He showed me the way he was doing it, which was much simpler, and I said, “Heck, there’s no sense using a character generator.” ‘Cause what he did was he decoded segments to make block lettering, numbering for score keeping [in Pong]. He really didn’t have need for anything else that was character oriented.

JL: Not really — I tried to sell Alan a character generator. He showed me the way he was doing it, which was much simpler, and I said, “Heck, there’s no sense using a character generator.” ‘Cause what he did was he decoded segments to make block lettering, numbering for score keeping [in Pong]. He really didn’t have need for anything else that was character oriented.

The first Pong machine was put into a beer joint. And Alan told me the first week that thing was in, coins were flopping out on the floor. The game I did using the F8 microprocessor was put into a pizza parlor down in a place called Campbell, California. And one of the features that it had was a coin jiggle function.

One of the things the [Atari] guys were telling me was that kids were coming in with piezoelectric shockers and shocking the machine to give them free games. Or they would take in a wire and jiggle it down in the coin slot. So he said he would love to have a way where that wouldn’t happen anymore.

What we did was take coins — it goes through the coin device and it hits a microswitch. It stays on the microswitch for a certain period of time before it drops down, right? We’d time that point of time that it would go through the microswitch, so the microprocessor on board would know whether it was a coin or somebody jiggling the switch. That was the way we had a coin defeat for it.

BE: Was that for your Demolition Derby?

JL: Yeah, that was for mine.

BE: When was the first time you saw a video game? Was it Pong, or…

JL: No, it was Nolan’s game called Computer Space. It looked like a big phone. And there was some talk about a game that was kept at the student union at Stanford — I never did see that one, though. It used a computer and some graphics functions — way too expensive to be in a consumer product.

BE: It’s really interesting that you were there at the birth of arcade games.

JL: I was also there when two gentlemen showed up — we used to have a computer club [The Homebrew Computer Club –ed.] that was in the Stanford Linear Accelerator auditorium once a month. And the two guys that used to come there all the time with their little toys — one guy was named Steve Jobs, and the other guy was named Steve Wozniak. There during the beginning.

BE: Did you attend any of those computer club meetings?

JL: Yes, I went to most of them.

BE: Did you talk to Steve Jobs and Wozniak back then?

BE: Did you talk to Steve Jobs and Wozniak back then?

JL: I was not impressed with them — either one, in fact. What happened was that when I had the video game division [at Fairchild], and I was the chief engineer, I interviewed Steve Wozniak for a job to work for us. Well, my guys were kind of impressed with him at first, and I said I wasn’t. Never had been.

[Update (2021): In a 2017 interview on my Culture of Tech podcast, Steve Wozniak denied that he ever applied to work at Fairchild and has no memory of ever meeting Lawson or seeing him at the Homebrew Computer Club. This doesn’t mean it didn’t happen, but Wozniak doesn’t remember it.]

BE: Were you the only black guy at those computer club meetings?

JL: Yes.

BE: Did you know any other black people in that field at the time?

JL: There was a guy who was around that time, and he’s dead now. His name was Ron Jones. He ended up pushing all kinds of side things. He was around. He was not in the industry, per se.

BE: So you said you weren’t impressed with Wozniak at the time. What was your impression of Jobs and Wozniak back then?

JL: Jobs was kind of a sparkplug. He was more business — he was more “push-this, push-that” kind of a thing. I think that his motivation is still there, the same way. He’s the sparkplug of Apple, right? Wozniak never was. But the guy who was the real hero that never gets mentioned is a guy named Mike Markkula. Mike Markkula was a multi-millionaire. In fact, he was one of the original founders of Intel. He also built Incline Village in Tahoe, and he ran Apple for a while.

BE: Mike gave them their first investment — their first seed money, right?

JL: Yes, he did. He is filthy rich, but a good guy. Really good guy.

BE: What position were you interviewing Steve Wozniak for at Fairchild?

JL: Just as an engineer. We had a bunch of engineers that were already there.

BE: What year was that?

JL: It was about the same time, ’73 or ’74.

BE: So he just didn’t get the job or you picked somebody else? Is that what happened?

JL: He was going to go away to — [his HP division] was moving to Corvallis [Oregon]. He was working for HP, and he was looking for a job to get away from HP. That was before they even started Apple up. Before they were on their own.

Video Games at Fairchild

BE: Lets get back to your career at Fairchild. How did the whole video game thing at Fairchild get started?

JL: I did my home coin-op game first in my garage. Fairchild found out about it — in fact, it was a big controversy that I had done that. And then, very quietly, they asked me if I wanted to do it for them. Then they told me that they had this contracted with this company called Alpex, and they wanted me to work with the Alpex people, because they had done a game which used the Intel 8080. They wanted to switch it over to the F8, so I had to go work with these two other engineering guys and switch the software to how the F8 worked. So, I had a secret assignment; even the boss that I worked for wasn’t to know what I was doing.

JL: I did my home coin-op game first in my garage. Fairchild found out about it — in fact, it was a big controversy that I had done that. And then, very quietly, they asked me if I wanted to do it for them. Then they told me that they had this contracted with this company called Alpex, and they wanted me to work with the Alpex people, because they had done a game which used the Intel 8080. They wanted to switch it over to the F8, so I had to go work with these two other engineering guys and switch the software to how the F8 worked. So, I had a secret assignment; even the boss that I worked for wasn’t to know what I was doing.

I was directly reporting to a vice president at Fairchild, with a budget. I just got on an airplane when I wanted to go to Connecticut and talk to these people, and I wouldn’t have to report to my boss. And this went on, and finally, we decided, “Hey, the prototype looks like it’s going to be worth something. Let’s go do something.” I had to bring it from this proof of performance to reality — something that you could manufacture. Also, a division had to be made, so I was working with a marketing guy named Gene Landrum, and sat down and wrote a business plan for building video games.

I was the number one employee. My set task was to work on the prototype and hire a bunch of people to work with me, most of which came from Fairchild. In fact, the big man asked me, “Where did these people come from?” And I said, “They were working here all the time.” He said, “They were?” I said, “Mmm hmm. All they needed was a reason to do something.” I just went out and talked to them.

So, it was an interesting thing, because the memory we used — 4K RAMS, dynamic RAMs — I would use four of them per system. Now, in making the pricing up, I used to go to MOS (even though Fairchild also made these things), and they were throwing out the ones that weren’t passing their tests. And I would go up there — literally with a little red wagon and two cardboard boxes — and I would load them up with RAMs: they’re throw outs, they’re garbage. And I’d take them to an outside test lab, and I got 90% yield out of their garbage can.

So, it was an interesting thing, because the memory we used — 4K RAMS, dynamic RAMs — I would use four of them per system. Now, in making the pricing up, I used to go to MOS (even though Fairchild also made these things), and they were throwing out the ones that weren’t passing their tests. And I would go up there — literally with a little red wagon and two cardboard boxes — and I would load them up with RAMs: they’re throw outs, they’re garbage. And I’d take them to an outside test lab, and I got 90% yield out of their garbage can.

So I was sitting there going, “Great, it’s for free!” [MOS] heard I was doing it for free, so they got in there and decided, “Uh uh, you’re going to pay for them!” I said, “You dirty rats.”

So the vice president I was working for, Greg, gets involved and said “I’ll take care of the negotiations over this.” He got in there and did a great negotiator job of two dollars per unit that we had to pay.

Well, one day I got tired of taking my engineers off their work to prove that the parts MOS were delivering were garbage, or no good. I was getting really pissed at them. Finally, one day they couldn’t deliver anything. So I asked for permission to go to Intel, who made the part too. One day, I walked into the vice presidents office and I said, “Want to see something?” He said, “What?” “Look at this. You are paying two dollars a piece for garbage that we can’t get. I can get them from Intel for a dollar ten.”

He said, “What?”

“Uh huh, you’re being taken.”

BE: And he was the one who did the negotiating, right?

JL: Yeah, right. I kept trying to tell him when I was in the ranks, “You know, our pricing is way too high. That’s one of the reasons why we get our lunch taken out. You don’t know how to make product cheap enough.”

The First Cartridge System

BE: When you started that video game prototype at Fairchild, was it always intended to be a home product, like a video game console for a TV set?

BE: When you started that video game prototype at Fairchild, was it always intended to be a home product, like a video game console for a TV set?

JL: It was always intended to be a home game.

BE: Had you seen the Magnavox Odyssey?

JL: Yep.

BE: And you perhaps wanted to do a product like that?

JL: Nope.

The Odyssey was a joke, as far as I’m concerned. It was the plug board thing — it had no intelligence. And it had overlays, remember? They put things the screen to play different games. What was paramount to our system was to have cartridges. There was a mechanism that allowed you to put the cartridges in without destroying the semiconductors. The mechanical guys that worked on that did a very good job.

BE: So that was a big issue at the time: plugging and unplugging a cartridge might…

JL: …cause an explosion on the semiconductor device — break down static charge, that kind of thing. We were afraid — we didn’t have statistics on multiple insertion and what it would do, and how we would do it, because it wasn’t done. I mean, think about it: nobody had the capability of plugging in memory devices in mass quantity like in a consumer product. Nobody.

BE: It was completely new then, wasn’t it?

JL: Yeah. We had no idea what was going to happen. And then we also had to stop putting [the chips] in packages. We had to put them on little boards where we’d put the chip down and we’d bond the chip to the board, then put a glob top on it. The package was a waste.

BE: Whose idea was it to do the cartridge in the first place?

JL: I always had that idea. We had a lot of people that did.

[Editor’s Note – 2/21/2015 – We now know that the initial idea for a video game cartridge actually came from two men, Wallace Kirschner and Lawrence Haskel, who worked for Alpex Computer Corporation and licensed the technology to Fairchild.

After Fairchild licensed Alpex’s technology, a team that included Ron Smith, Nick Talesfore, and Jerry Lawson refined the technology and turned it into a practical, commercial product.

So the credit for the first cartridge should technically be shared among these five men — and not by Lawson alone, as many have misinterpreted since I published this interview in 2009.]

BE: It seems that — from what I know, RCA released a system that had cartridges around the same time as the Channel F.

JL: RCA was behind us. In fact, it was a piece of junk. I’ll tell you a funny story about RCA. We introduced our game, and RCA followed six months later in the Winter CES show. At that show in Chicago, RCA presented their Studio II. I had an invitation that said, “Hey, the RCA game is here.” Well, I wanted to see that. It was being shown in a suite. And I went up to the suite and walked in. They had their game there, and this guy looks up and sees me with a Fairchild badge on, right? And I’m 6’6″, 280 pounds. This clown charged me and tried to wrestle me to the ground. And I banged him on his head! I said, “If you want me to leave, I’ll leave!”

JL: RCA was behind us. In fact, it was a piece of junk. I’ll tell you a funny story about RCA. We introduced our game, and RCA followed six months later in the Winter CES show. At that show in Chicago, RCA presented their Studio II. I had an invitation that said, “Hey, the RCA game is here.” Well, I wanted to see that. It was being shown in a suite. And I went up to the suite and walked in. They had their game there, and this guy looks up and sees me with a Fairchild badge on, right? And I’m 6’6″, 280 pounds. This clown charged me and tried to wrestle me to the ground. And I banged him on his head! I said, “If you want me to leave, I’ll leave!”

And what I saw was a laugh. They had this game — it was in black and white. It looked horrible. So, the next day, he came down to our booth. And when he came down to our booth, I jumped the counter, heading for him. And he started running! [laughs] I said, “Ah, there he goes.”

BE: You said that Channel F had already been released, right?

JL: Oh yeah. Well, the biggest part of getting the Channel F released was getting through the FCC. That was a job in itself. It was the first microprocessor device of any nature to go through FCC testing. And I — believe me, I got some gray hairs over that. The FCC was really hard on us. And Al Alcorn came down — it was funny when they first saw it — Al, Nolan, and the [Atari] president then — at the Chicago show. They came down to me and said, “Lawson! It’s cool, except the only thing we dig is the hand controllers.” And Al told me, he said, “Oh, boy, that little noise you’ve got there on the screen, boy, you’re really going to have to get rid of that — you’re gonna have trouble with the FCC.”

And I had to leave the show early to go to the FCC. Because the FCC — oh boy — it cost, at that point, a thousand dollars, and the spec they had was one microvolt per meter of spurious signals you couldn’t overcome. And if you had any more than that, you were in trouble.

The problem was — Texas Instruments, years later, couldn’t make that spec. So guess what they did? They lobbied and got them to change the law. I was so mad, I couldn’t see straight. ‘Cause that was what keeping a lot of people from jumping in the market, including RCA. They couldn’t pass the test.

We had to put the whole motherboard in aluminum. We had to make an aluminum case for it, we had to have bypasses on every lead going in and out of the thing. It was unreal, some of the stuff we had to do. We had a metal chute that went over the cartridge adapter to keep radiation in. Each time we made a cartridge, the FCC wanted to see it, and it had to be tested.

BE: Wow. Every single cartridge?

JL: Every single cartridge.

BE: By ’77, when the Atari VCS was released, do you think they had to get their cartridges tested, or was that out the window?

JL: I’m sure they had to.

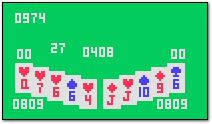

BE: What did you think about the Atari VCS when it came out?

JL: The VCS had some good features in it, but by and large, as far as for graphical display, it was substandard. They had ways of doing things with — you use things known as sprite technology. They could make high resolution characters, but they couldn’t put a bunch of stuff on the screen at the same time. So, as a result — one of the games they tried to compete with us, and they did a very bad job, was Blackjack. Blackjack looked horrible.

JL: The VCS had some good features in it, but by and large, as far as for graphical display, it was substandard. They had ways of doing things with — you use things known as sprite technology. They could make high resolution characters, but they couldn’t put a bunch of stuff on the screen at the same time. So, as a result — one of the games they tried to compete with us, and they did a very bad job, was Blackjack. Blackjack looked horrible.

Of course, they did things that tried to offset that. You can’t blame them for that, right? And their first game had a beautiful sky and objects running across it. It looked very cool. But it really wasn’t anything. But it was the best graphic looks that the game [could do]. Ours looked like little players, and things, you know.

BE: How much total RAM did the Channel F have in it?

JL: 16K [kilobits]

[Editor’s Note: As it turns out, the Channel F had 64 bytes of main RAM and 16 kilobits (or 2 kilobytes of video RAM). During the interview, I misunderstood that Lawson was speaking of kilobits and not kilobytes.]

BE: Really? 16K? That was a lot at the time. I think the VCS had 128 bytes of RAM.

JL: See, our memory was used as a screen. The screen was memory. What you were doing when you played our game, you were actually putting symbology in a memory, and that memory was being displayed on screen. What you looked at when you were looking at the screen was an array of memory so-many-bits high by so-many-bits deep. In fact, when we had to move a character around, we had a thing we called “self-erasing characters.” Now what we would do is black out a square — say eight by eight — and around that eight by eight would be a border or background, and the symbology was put inside of it. So every time it moved, it would automatically erase the previous position. If we hadn’t done it that way — like we tried to fill it in — each time we moved it, we’d have to erase the last position it was in. If we did it that way, we ended up having objects that look like they’re jumping around and flashing.

JL: See, our memory was used as a screen. The screen was memory. What you were doing when you played our game, you were actually putting symbology in a memory, and that memory was being displayed on screen. What you looked at when you were looking at the screen was an array of memory so-many-bits high by so-many-bits deep. In fact, when we had to move a character around, we had a thing we called “self-erasing characters.” Now what we would do is black out a square — say eight by eight — and around that eight by eight would be a border or background, and the symbology was put inside of it. So every time it moved, it would automatically erase the previous position. If we hadn’t done it that way — like we tried to fill it in — each time we moved it, we’d have to erase the last position it was in. If we did it that way, we ended up having objects that look like they’re jumping around and flashing.

A lot of little things we used to do were different. Our hand controllers were special. They were analog equivalent, but they were digital. And somebody asked how we did that. Well, we would drive the objects. In other words, when the [switch] closed in a direction, we would send the object in that direction. We’d send it fast, then we’d slow it down, so that it would have a kind of a hysteresis curve. We needed to do that for the human factors of using the hand controllers.

The hand controllers had a lot of — nobody has duplicated one yet. They’ve used them in other things. The hand controller had eight positions: up, down, left, right, forward and backward left and right. Eight positions.

BE: Do you know the history of Atari’s joystick and how it compared to the Fairchild hand controller? Who made the first home console joystick? Was it Fairchild?

JL: Yep. Ours was digital. Digital meaning there was no fixed position. If you had a regular hand controller that is run with resistors or pots, you move the hand controller and leave it alone, that object would say, “OK, I’m staying in that position.” Ours would not. In other words, every time you’d move it, and let go, it would stay where it is However, the hand controller would be back in neutral position again. So you had to get used to that operation, knowing how to operate it.

BE: Who designed the controller for the Channel F?

JL: I designed the prototype. The original controller was designed by a guy named Ron Smith. Mechanical guy. The case of the controller was designed by a guy named Nicholas Talesfore, an industrial designer.

BE: What was your official title or position when you were working on the Channel F?

JL: I was director of engineering and marketing for Fairchild’s video game division. I was in charge of all the new cartridges, how they were made, and what the games were.

BE: What was the atmosphere of your office like at Fairchild when you were developing the Channel F?

JL: Well, I was always considered to be a renegade. I mean, I had many people from Fairchild’s operation up in Mountain View come down and tell me how to operate a business. I’d send ’em home with their tails wagging.

One of the things I told them, very simply, was that some of the biggest problems any company has in development is having all these tin gods that come down and tell you how to do things. And one of the reasons they can never develop anything is because of these tin gods. It’s not enough to say, “Here’s a business. Run this business.” You have all these people telling you what you should do and how you should do it.

IBM was smart enough that when they developed the PC, they put a whole group in Boca Raton and left them alone. If they hadn’t, they wouldn’t ever had a PC. It would have come out looking like a machine that needed to be in somebody’s office, not somebody’s home.

BE: Did you have any contact with Ralph Baer or Magnavox in the ’70s?

JL: I met Ralph Baer maybe 6-7 years ago — maybe more than that — at the Classic Gaming Expo. I met him there on a panel. In fact, what they did is that I was a big secret a lot of times, because people didn’t know who I was. And what happened was they had me come there introduced by this Japanese guy that was with the group, and he said, “You guys want to meet the person who started the cartridge business? Jerry, stand up.” And I stood up and joined them on the dais.

In fact, there’s one cartridge that’s really funny. The guy paid — we did a cartridge when I had my own company called Videosoft. It was a 2600 cartridge — it was a color bar generator.

BE: Like a TV test pattern kind of thing?

JL: Yep. At the vintage show in San Jose, a guy comes up to me and he says, “Hey! You’re Videosoft, aren’t ya? You got any more of those Color Bar cartridges?” I said, “Nah, I haven’t got one.” He found one at the show, and he came up to me and said, “Autograph this for me?” I said, “Yeah, sure.” He got a silver ink pen, and I autographed it. The next day, I was giving a talk from the dais, and another guy said, “Hey, did you autograph a cartridge yesterday?” I said, “Yeah. Why, did you buy it?” He said, “Yeah. Since it’s got your autograph on it, I paid $500 for it.” Holy Jesus, right? My wife was sitting there going, “You got any more of those?” [laughs]

BE: Yeah, that would be a good business to get into.

Impact of Race on Profession

BE: Did you experience any difficulties in your career because of your race?

JL: Oh yeah. There’s two ways I used to experience it. First of all, I’m a big guy. So not too many people confronted me face to face. But I’ve had instances where I’ve walked into places where they didn’t know I was black.

I’ll give you an example. Not that the guy was a racist, but a guy named John Ellis, who was one of the Atari people. In about, oh, 1996 or 7, a law firm in Texas hired me as a consultant. And they were going to sue Nintendo. And they told me they want to bring John Ellis in too, ’cause he’s from Atari, and I go, “Oh, fine.” They said, “You know John Ellis?” I said, “I know John — very well.”

I’ll give you an example. Not that the guy was a racist, but a guy named John Ellis, who was one of the Atari people. In about, oh, 1996 or 7, a law firm in Texas hired me as a consultant. And they were going to sue Nintendo. And they told me they want to bring John Ellis in too, ’cause he’s from Atari, and I go, “Oh, fine.” They said, “You know John Ellis?” I said, “I know John — very well.”

So the next day, John comes in the room, sees me, and says, “Hi Jerry.” And he looked kind of strange. I said, “What’s the matter with you, John?” He said, “I’ve always known you as Jerry Lawson. I didn’t know you were the same video game guy Jerry Lawson — I didn’t know you were black!” And I said, “Huh?” He said, “Al Alcorn, Nolan Bushnell, talked about you — all of them talked about you — Joe Keenan. But they never said you were black.” I said, “Well, I am.” He said, “I don’t know whether they did you a favor or not.” I said, “Well I don’t go around telling everybody I’m black.” I just do my job, you know?

With some people, it’s become an issue. I’ve had people look at me with total shock. Particularly if they hear my voice, because they think that all black people have a voice that sounds a certain way, and they know it. And I sit there and go, “Oh yeah? Well, sorry, I don’t.”

BE: Why do you think there’s so few black people working in engineering?

JL: I think what has happened is that engineering is a thing that has never really appealed to black people directly, because they’ve never had…

You see, I grew up in a different environment. My mother — she invented busing. When she went to a school, she would interview the teachers, the principal, and if they didn’t pass her test, I didn’t go to that school. She once put me in a school called P.S. 50. Turns out Mario Cuomo went to that school. He was a little older than me, and I didn’t know him at the school, but he went to the same school. My mother — now get this now — the school was 99% white. My mother was the president of the PTA.

You see, I grew up in a different environment. My mother — she invented busing. When she went to a school, she would interview the teachers, the principal, and if they didn’t pass her test, I didn’t go to that school. She once put me in a school called P.S. 50. Turns out Mario Cuomo went to that school. He was a little older than me, and I didn’t know him at the school, but he went to the same school. My mother — now get this now — the school was 99% white. My mother was the president of the PTA.

We didn’t even live in the neighborhood. I had a phony address, I used to go halfway cross town to go to school and to go home. I went up ’til the 6th grade, then I went to a junior high school that turned out to be really bad. I was in there for six months, and my mother came to school one day. She talked to the principal, talked to the teacher, and walked in the classroom. She nodded toward me, and I go, “Oh well, that’s it.” And I wasn’t going to stay in that school. So I went to another school.

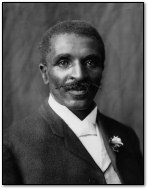

But one of the things she had long since said was that the black kids were put under an aroma of “you can’t do something.” It was something that she felt would not help them with any kind of inspiration to go anywhere. When I was in P.S. 50, I had a teacher in the first grade — and I’ll never forget that — her name was Ms. Guble. I had a picture of George Washington Carver on the wall next to my desk. And she said, “This could be you.” I mean, I can still remember that picture, still remember where it was.

But one of the things she had long since said was that the black kids were put under an aroma of “you can’t do something.” It was something that she felt would not help them with any kind of inspiration to go anywhere. When I was in P.S. 50, I had a teacher in the first grade — and I’ll never forget that — her name was Ms. Guble. I had a picture of George Washington Carver on the wall next to my desk. And she said, “This could be you.” I mean, I can still remember that picture, still remember where it was.

Now, the point I’m getting at is, this kind of influence is what led me to feel, “I want to be a scientist. I want to be something.” Now, I went to another black school and talked to kids who were in the neighborhood, and they did nothing like this. They never went out anywhere, they never knew anything. The kids I worked with, and went around with, and played with — they did different things, right? They were looking through microscopes. They’d go outside in a field — do something, right? These would not do that. All they did was play baseball or football.

So I think my mother had a lot to do with it. She was very effective at the board of education, because she would tell them off. She’d tell ’em, “Look. My school needs this, and that’s it.” She’d long since found that the squeaky wheel gets all the oil. She was president of the PTA for about four years.

BE: And that was in the 1950s?

JL: The ’50s, yeah. So anyhow, my mother was very key to that. In fact, she died a very young age. It was the part of the eulogy I gave her about some of the things she had accomplished.

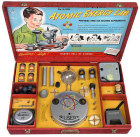

I remember as a kid, I wanted to get an atomic energy kit. Gilbert Hall of Science made one. It had a Geiger counter and a Wilson cloud chamber. A hundred bucks. My mother tried to get it for me for Christmas, but finally sat down and told me, “I can’t do it.” I understood. But she got me a radio receiver, a [Hallicrafters] S-38. That’s what got me into amateur radio. From then on, I built converters, antennas, everything else. That is the heart of what I started out with.

I remember as a kid, I wanted to get an atomic energy kit. Gilbert Hall of Science made one. It had a Geiger counter and a Wilson cloud chamber. A hundred bucks. My mother tried to get it for me for Christmas, but finally sat down and told me, “I can’t do it.” I understood. But she got me a radio receiver, a [Hallicrafters] S-38. That’s what got me into amateur radio. From then on, I built converters, antennas, everything else. That is the heart of what I started out with.

I ran into one black man who did help me, and his name was Cy Mays. Cy worked as a motorman in the subway system in New York. He was a buddy of one of the guys who ran Norman Radio. And I used to come in to Norman Radio and — I used to have a red baseball cap — and they said, “Red Cap’s here!” And he came out and saw me and said, “Why you getting all this stuff?” I said, “I just got my license.”

“You just got your ham license?”

“Yeah.”

“Have you got a car or some kind of conveyance, or something?”

I said, “Yeah, my dad does.”

He said, “Ok, here’s my address. Come around this Sunday.”

He had more stuff in his garage and his basement…it was like going through a goodie land. “Take whatever you need.”

BE: What advice would you give to young black men or women who might be considering a career in science or engineering?

JL: First of all, to get them to consider it in the first place. That’s key. Even considering the thing. They need to understand that they’re in a land by themselves. Don’t look for your buddies to be helpful, because they won’t be. You’ve gotta step away from the crowd and go do your own thing. You find a ground, cover it, it’s brand new, you’re on your own — you’re an explorer. That’s about what it’s going to be like. Explore new vistas, new avenues, new ways — not relying on everyone else’s way to tell you which way to go, and how to go, and what you should be doing.

JL: First of all, to get them to consider it in the first place. That’s key. Even considering the thing. They need to understand that they’re in a land by themselves. Don’t look for your buddies to be helpful, because they won’t be. You’ve gotta step away from the crowd and go do your own thing. You find a ground, cover it, it’s brand new, you’re on your own — you’re an explorer. That’s about what it’s going to be like. Explore new vistas, new avenues, new ways — not relying on everyone else’s way to tell you which way to go, and how to go, and what you should be doing.

You’ll find some people out there that will help you. And they’re not always black, of course. They’re white. ‘Cause when you start to get involved in certain practices and certain things you want to do, you’re colorless.

In fact, one of the funny stories about is that for years, people heard me on the radio, and didn’t know I was black. In fact, Hal — a good friend of mine who just passed way — took me to what is called a “bunny hunt.” A bunny hunt is where a guy has a hidden transmitter, and you try to locate where he is. The people trying to find him all go to a diner and talk to each other; they call it “having an eyeball.” Well, I went with Hal one time, and a bunch of guys all over the diner came down to see him. One of them says, “Hey Hal, how ya doing?” And Hal says, “Oh, fine.” And he said, “How are you, sir?” And I said, “I’m fine.” And he said, “What did you say?”

“I said ‘I’m fine.'”

And he goes, “Jerry? K2SPG Jerry?” He went running down the end of the bar and came back with everybody. And they all went, “You’re Jerry?” I was like, “Yeah. And this one girl, she said, “Oh God, I had a picture of you — I was in love with your voice.”

“Oh, you were?”

“And I had a picture of you, and you were about 5’7″, blond hair and blue eyes.”

“God, you’re way off on that, aren’t you?” [laughs]

BE: So I guess you have to be brave in some ways to be a black scientist. It seems like it would go against the tide of culture.

JL: The point of anything by yourself is that you have to be brave to go by yourself, don’t you? You’re not going to get reinforcement from peers, right? Except for the new peers you find as a result of going through this.

I mean, normally, the guys on the corner that go play basketball are not gonna be your buddies in that. And that’s how they mark things too. It’s unfortunate that they all think they’re gonna be members of the NBA. I try to tell them, “be.”

BE: How many kids do you have?

JL: Two: a son and a daughter.

BE: Did any of them follow you into engineering or something similar?

JL: One is now following me, and that’s interesting. He went through Morehouse in Atlanta and graduated as a programmer. Computer science. Just recently, he decided to go back, because he wanted to do electronics. He’s taking his master’s and he’s becoming an A-student at Georgia Tech. And he calls me — he does microprocessor work now and all these things that really appeal to him, and he says, “You know, pop? I like this stuff, and my wife calls me Little Jerry.”

My daughter — she was an athlete that kinda blew it. ‘Cause what happened, is when she was ready to go to the Olympics, she got all fouled up. The girl that she was racing against ended up in the Olympics — but she beat ’em all. She has three track & field records at the high school she went to; they still stand.

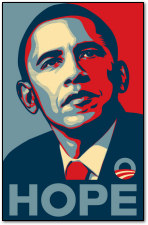

BE: How do you feel about Obama as President?

BE: How do you feel about Obama as President?

JL: Let me put it this way: Obama was the best qualified guy, period, of any color. Obama was put in that office position not because he’s black, but because he’s the best qualified, and a lot of white people put him there. If it wasn’t for the white people, he wouldn’t have been there, because the black people can’t put you in that office. If anybody thinks that because he’s black, he’s going to turn around and make everything black, he’s not. It’s not his way. And his heritage is half-white anyhow, right? So it’s not even that — even if he was an all-black man, he still wouldn’t do that.

Obama is needed because, all of a sudden — I think — it’s amazing how much people have changed their attitude about what’s going on in this world. I’m hoping that he can straighten out a lot of things with his attitude. Because one of the things that the government does, or the man at the top does, is to set the tone of what’s gonna happen.

Lawson Today

BE: What are you up to these days?

JL: Well, I used to work with Stanford in the mentor program, working with kids to put two satellites in space already. Other than that, I do laser work, and I’m getting ready to write my book.

BE: Have you played any video games since the 1970s? Have you kept up with video games?

JL: I don’t play video games that often; I really don’t. First of all, most of the games that are out now — I’m appalled by them. They’re all scenario games considered with shooting somebody and killing somebody. To me, a game should be something like a skill you should develop — if you play this game, you walk away with something of value. That’s what a game is to me.

JL: I don’t play video games that often; I really don’t. First of all, most of the games that are out now — I’m appalled by them. They’re all scenario games considered with shooting somebody and killing somebody. To me, a game should be something like a skill you should develop — if you play this game, you walk away with something of value. That’s what a game is to me.

If I was to say intelligence was a weight and say, “Let’s take intelligence, weigh it in pounds, and say it’s a hundred pounds.” The way we measure intelligence today is if I have a hundred pounds of intelligence and I get from you 99 pounds, you’re considered bright, right? My feeling is what “bright” is or what “genius” is — if I give you a hundred pounds of intelligence, you give me back 120. That means you take what you’ve taken and gone beyond that. You’ve learned other things, correlated the pieces, and put it together and added something to it. That’s genius.

And what’s wrong many times today is that we don’t have any basis for teaching that correctly. See, we’re taking away from children’s imaginations. Video games today — they don’t even want to see anything unless the graphics are completely high-toned, right? It used to be, “Oh, well that looks like a car.” Well, looks like one, you know? No, they want to see a car, they want to see wheel spinners on it, and all the detail — infinite detail.

BE: How has being a designer on the Fairchild Channel F changed your life?

JL: It made me go into business for myself — I can tell you that. Videosoft I had for a couple years, I started that. We did cartridges for the 2600 and for Milton Bradley.

Also, I remember one time I was in Las Vegas, walking down the strip. A black kid came up to me and said, “Are you Jerry Lawson?” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “Thanks.” And shook my hand and walked on past me. And I thought I may have inspired him.

My son actually nominated me as a fellow at the Computer Museum. Whether or not it goes anywhere, I don’t know. But I feel that I’ve got to get that done. I’m writing my story because I think that when kids go there — black kids — and they see somebody black, it will make a big difference on them.

My son actually nominated me as a fellow at the Computer Museum. Whether or not it goes anywhere, I don’t know. But I feel that I’ve got to get that done. I’m writing my story because I think that when kids go there — black kids — and they see somebody black, it will make a big difference on them.

—

[ Update: 2/21/2015 – For more on the creation of the Channel F, read “The Untold Story of the Invention of the Game Cartridge” by Benj Edwards at FastCompany.com. ]

February 25th, 2009 at 5:47 pm

Thank you so much for this. I had never heard the name before, but now I can’t stop looking around. Someone should make a movie about this man.

February 25th, 2009 at 6:03 pm

Very interesting!

February 25th, 2009 at 6:30 pm

Great interview. Thanks, Mr. Lawson, for taking the time to talk to someone, and for having so much to say. And thanks VC&G for putting it together.

February 25th, 2009 at 9:49 pm

Outstanding RW, quality.

February 26th, 2009 at 12:07 am

That was a genuinely engaging story. I too was unfamiliar with Mr. Lawson’s work, but I am glad to learn yet another piece in the early history of personal computers and video gaming. One of the things that stands out to me is his assessment of Steve Wozniak as being unimpressive. Jobs, I can understand, but Wozniak? I’d like to hear more about why that was the case. Judging from their backgrounds, I’d have figured they’d make great friends.

But overall, Mr. Lawson sounds like a very interesting guy and thanks for sharing his story with us.

February 26th, 2009 at 1:15 pm

That was fascinating — I knew the name Jerry Lawson, but that was about it. Thanks for doing the interview, Benj, and Mr. Lawson, thanks for sharing so much!

February 26th, 2009 at 4:36 pm

I guess you’ll have to change your anti-bot code now, Benj.

February 27th, 2009 at 9:50 am

Thank you for putting this story here really great and inspiring for anyone its a life lesson.

February 28th, 2009 at 2:28 pm

This was a great interview. I remember seeing the name in my old computer gaming mags from years ago. It was very interesting to read his life story. He definitely deserves to be featured in the Computer History Museum.

February 28th, 2009 at 5:52 pm

Another Amazing article Benj! It’s articles like this that keeps your site in my bookmarks toolbar, and keeps me checking again and again to catch the next one. Keep em coming!

March 1st, 2009 at 3:41 pm

Thanks for that, Benj. Excellent interview. I look forward to Mr. Lawson’s book.

March 1st, 2009 at 4:42 pm

Jerry

Dick Kors forwarded this link to me this morning. Enjoyed reading your interview and learned so much more about you, even though I worked with you at Fairchild in the early 70s getting your RVs outfitted and road-ready. Yours is a fascinating and inspiring story.

March 1st, 2009 at 6:16 pm

Jerry

Remember that bacholer party in the Santa Cruz mountains? Remember “made in fairchild”?

Ring me up, lets have lunch.

March 2nd, 2009 at 3:19 pm

Jerry,

I got the link to your story from Geri Hadley. Yours is a fascinating story. So glad Benj Edwards did this, and I hope it will make your history known to new groups. I remember much of the Channel F game history, and the FMC RV conversion. Cheers to you!

March 2nd, 2009 at 4:30 pm

Jerry is my dad too.

March 2nd, 2009 at 9:07 pm

Yo Jerry,

I also got this link from Gerri. Nice job by both you and Benj Edwards.

By the way, I didn’t know you were black, man.

Regards,

Don

March 3rd, 2009 at 1:02 am

Heh Jerry, Now we’ve heard… the rest of the story. Still have one of those hand controllers in my drawer. Can’t seem to get rid of the darn thing.

All the best,

Gary

March 3rd, 2009 at 3:34 am

I have always been proud of my friend Jerry, and always introduced him as the person who created video games. I met him when I worked at Fairchild. There should be a movie about him and inspire particularly Black youth about science and engineering. It is my honor and pleasure to call him my friend. See you soon!

Rosiland

March 8th, 2009 at 11:46 pm

Great read. Very inspiring.

March 10th, 2009 at 10:04 pm

As a teacher with experience teaching in all black schools in Prince George’s County, Maryland, I can tell you that we need more stories like this to inspire the African-American youth of today to pursue careers and science in electronics. Thanks, Jerry.

March 11th, 2009 at 6:20 pm

Very nice interview. Jerry is one amazingly talented guy.

March 11th, 2009 at 7:40 pm

Excellent interview about a fascinating figure. Thanks to Mr. Edwards for conducting it and to Mr. Lawson for participating, it was a really great read.

March 11th, 2009 at 9:30 pm

I’ve seen Jerry talk about the Fairchild (videogame) days at the Classic Gaming Expo twice now, and was fascinated both times. It’s cool that he’s finally getting his due. Nice interview!

March 18th, 2009 at 7:10 pm

I’ll never forget Jerry’s speech at CGE 2004. First I had to help him up to his seat at the podium. Then just as he began to talk, the fire alarm went to off so I had to quickly get him back down to his wheelchair so we could evacuate the building. Unofrtunately, less people returned to hear Jerry talk after the fire drill.

By the way, in this article Jerry mentions another black man in the industry named Ron Jones. Ron Jones later founded Songpro, a company that had released a peripheral that turned the Gameboy into an MP3 player. I hadn’t been aware that he had died.

May 21st, 2009 at 3:12 pm

Wow… how could I not have heard of this amazing gentleman?!

Thank you, from everyone from my generation who ever picked up a controller. We are in your debt, sir.

June 21st, 2009 at 12:08 pm

Interesting article, got linked over from kotaku and read every word. Some interesting perspectives and neat to hear the history of videogames from someone who has been around it for so long.

June 22nd, 2009 at 12:01 am

While I knew of the Fairchild Channel F, I am ashamed to say that I did not know of the man behind it. Thank you Benj for bringing this to light, and thank you Jerry for being who you are. I hope I can thank you in person someday. 🙂

June 22nd, 2009 at 4:26 pm

What a great article. He says he’s writing a book. That looks like it’d be a good read.

June 29th, 2009 at 7:16 pm

Great interview.

Love the cruise control story. Clowns indeed.

I will buy his book in a minute.

October 12th, 2009 at 12:08 pm

Jerry was correct about the 16kbits of VRAM in the Channel F. It is arranged as a 128x64x2 bit frame buffer. Oh for a frame buffer on the 2600.

The CPU had a 64 byte internal scratchpad that allowed register windowing and a cheap 2 chip (CPU/ROM) system. Brilliant stuff for 35 years ago.

October 16th, 2009 at 12:15 pm

I really loved this interview. It feels like you honored a great man (with what I did read). Well done 🙂

November 19th, 2009 at 1:16 am

I ran across this interview while surfing and thought I’d respond. I worked with Jerry Lawson at Fairchild in 1977 (in the Exetron Division run by Don Brown under Greg Reyes) and think the world of Jerry as did his group. The details of this article are accurate and the article portrays his down home management style. The early industry was fun because of people like Jerry Lawson. After 30 plus years in the industry I’m amazed at how many important contributors are never fully recognized.

P.S.

I was on the IC design team that later integrated and cost reduced the original channel F with the 9101/9102 chip set.

January 18th, 2010 at 4:35 pm

I think this gentleman should be on a stamp someday. I happened across

this webpage doing some research in an unrelated field. I hope the best

on your book and much applause for the mentoring project(s).

June 1st, 2010 at 12:08 am

I wanted to get in touch with Jerry’s assisstant–I have his card but can’t find it. This is James, I uploaded videos of Jerry in the past and did an interview with him recently. I wanted to ask his tall assistant about some specific disks–please give me an email.

January 5th, 2011 at 2:13 pm

Videos on Jerry Lawson and his Channel F games

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-2498129174652261598#

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=6585977467001963251#

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=4639425208915226542#

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=6779946324333780961#

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MLrsLuMYfsc&p=DD55F9B0B931235D

February 16th, 2011 at 10:09 am

The moment I found this article I began to cry. I was overwhelmed with a gratitude and respect. Yet dismayed by the unjustified omission of Jerry Lawson from the History of our incredible Industry. I am ashamed of myself the chairman of the International Game Developers Association’s Diversity advisory board as well I sit on the steering committee for the Microsoft Blacks In Gaming Group seven years in the position and not once did I hear about Jerry. For sure we will be contacting him for the Game Developers Conference Minority SIG to honor him. He is a true treasure to all in the video game industry. Thank you sooooooo much for your article.

Peace,

Joe Saulter

April 11th, 2011 at 2:19 pm

Very sad news … Jerry Lawson died April 9th 2011. He will be sorely missed.

Here is a link to a recent interview with Jerry by the San Jose Mercury News.

http://www.mercurynews.com/business/ci_17531389?nclick_check=1

Regards,

david.

April 11th, 2011 at 9:16 pm

This was an excellent read. I don’t know why Mr. Lawson isn’t listed with other black inventors, he’s a very big part of a very big (and growing) industry.

As a black youth, everything he said about going your own path I have experienced myself. Unfortunately, the media has affected our self-perceptions for the worst. It is sad that in 2011, I go to my classes at university and find myself the only black male in the room/lecture hall. It would be great for his amazing life to get more exposure, his story is really touching.

RIP Jerry Lawson and may God be with your family.

April 11th, 2011 at 10:41 pm

RIP, Mr. Lawson. I regret that it was only now that I had the chance to know of you and your legacy. Thank you for your amazing influence and perseverance.

One thing I was interested in after reading this article was the book he was preparing to write. I hope that there’s at least a draft of it somewhere that can be finished and brought to press.

April 12th, 2011 at 12:55 am

I am sorry to say that I never did get a chance to meet you in person, Mr. Lawson. I can only hope that your final moments were spent with those you love and those who love you back.

You were and will continue to be a modern-day hero.

April 12th, 2011 at 1:58 am

Great interview –you get a sense of the man. It makes me wish I’d known more about him earlier. RIP, Mr. Lawson.

April 12th, 2011 at 7:19 am

I’m glad I found out about him. Thanks.

Rest in peace, Sir.

April 12th, 2011 at 12:46 pm

As a fellow ‘ham’, I’m impressed with the imfluence amateur radio had on Jerry’s youth. Ham radio has been a ‘start’ for many an engineer and tinkerer alike. I would like to think it was Jerry’s open mind and kind demeanour that marked his personality and career, and less his colour. His life is movie material indeed.

April 12th, 2011 at 2:15 pm

What a great interview. I never new much about the Channel F but always had a mild curiosity. Thanks to this piece I now know some more about it and about Jerry Lawson too. Fascinating person, and an equally fascinating history!

April 13th, 2011 at 3:52 am

An inspiration to all. All of us can take a lesson or two from your life story. RIP, Mr. Lawson.

April 14th, 2011 at 11:33 am

Great interview. I certainly hope Mr. Lawson was able to finish his book before he passed away. That is a story just begging to be made into a movie!

April 14th, 2011 at 3:52 pm

I find it hard to believe with all the gaming systems I’ve played and owned throughout my life, that I never stopped long enough to research the beginnings of it all or learned you were catalyst. I too, was a young black child with a keen interest in electronics, in a rough neighborhood surrounded by people that called me a square for not spending all my free time at the basketball courts. I wish I would have known about you before today. Hearing the story of your mother and her determination, and your successes was inspiring. I can’t wait to tell my son about you when I get home…and tell him it’s time to turn off the PS3. He has expressed to me before that he wanted to become a game developer. Maybe hearing about you will inspire him to reach that goal.

With sincere regards, Thank you Mr. Lawson!

May you Rest In Peace.

Omny

April 14th, 2011 at 7:52 pm

I was the industrial designer responsible for the styling and ergonomics for the Channel F System of hand-controllers, game console as well as the the inserted video cartridges. Ron Smith the ME on the team did all the mechanical engineering for the hand controllers internal switches and zero force cartridge connector system. I also had responsibility for all the graphics and labeling and instruction manuals so I worked closely with Jerry from the very beginning with Gene Landrum even before Fairchild decided to started this division. Jerry was a great guy to work with and especially travel with. JHe was truly a unique individual who always had a quick tory or two punctuated with his infectious laugh. I was very lucky to be associated with Jerry and the Channel F team to contribute to the beginnings of the Video Game industry.

Jerry will be missed but he left quite a legacy as all the Channel Team did.

April 14th, 2011 at 9:43 pm

Now this is a story just waiting to be a movie, I agree. I hope his kids will tell his story via Book & Film.

As an IT Professional who’s interest started due video games ( and my dad getting me a Spectrum Sinclair 45K RAM as a kid). I feel honoured / proud to be privy to your story.

Mr Lawson as an industry pioneer/ inventor WELL DONE.

For being an inspiration to all regardless of race WELL DONE.

As a black man passing on your experiences to the next generation WELL DONE

RIP bro your memory lives on.

DuCane Maximus. (UK)

April 14th, 2011 at 11:47 pm

We need more moms like Jerry’s. Of all colors.

April 15th, 2011 at 2:13 am

While I am/was involved with video game development I didn’t know who Jerry Lawson was until I read your article here.

What a great person Jerry is/was.

He sounds like a very down to earth, no nonsense, honest and truthful kind of guy.

And must have been one hell of a practical engineer.

A successful and uplifting story.

Also credit to Benj Edwards for being such a good interviewer.

Not being of the craft, I still picked up on this.

Your not lame like those “talking heads” on TV and magazines.

You ask questions for things that I and I’m sure others find interesting.

Like asking extra questions about race and such that crosses the mind.

P.S. I found your site http://www.benjedwards.com and started to read everything there.

I Googled “Jerry Lawson book” and found nothing.

Any news of Jerry’s book? I want to read it.

Assuming it’s not done/out, and there is enough to complete one I wonder if his son would get it out.

Benj (if you read this) would get involved with?

Great man, great article.

Thanks,

April 15th, 2011 at 7:44 am

WOW…Thanks so much for such a great article. Just like the other readers, I’m sadden that I didn’t hear about this man before his death. RIP Mr. Lawson.

Martin

April 15th, 2011 at 8:33 am

Thanks for the kind words, Kevin (and everyone else who commented on the interview). I really appreciate it.

I’ll post about Lawson’s book when I find out more.

April 15th, 2011 at 8:57 am

Jerry Lawson definately belongs in the Computer Museum. If there is a medal for perseverance it would have been an honor to have pinned it on his chest. I would very much like to buy his book for my grand kids. Thanks Jerry for all the games.

April 15th, 2011 at 12:40 pm

Thank you for this wonderdful artical.