Vintage Computing and Gaming is 20

November 2nd, 2025 by Benj Edwards Greetings, fellow retro tech fans. 20 years ago today, I launched Vintage Computing and Gaming. The origins of the site have been well-covered elsewhere, so I’ll spare you the rehash.

Greetings, fellow retro tech fans. 20 years ago today, I launched Vintage Computing and Gaming. The origins of the site have been well-covered elsewhere, so I’ll spare you the rehash.

Just kidding, that was a rehash. I copied and pasted that first paragraph from my 15th anniversary post and changed the number. 🙂

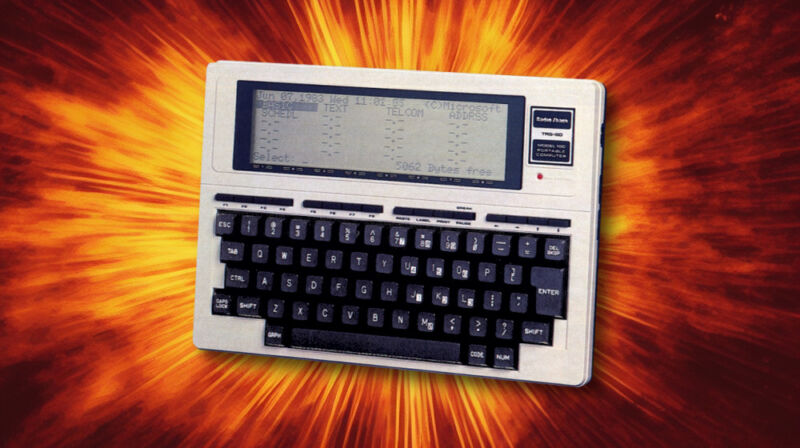

But seriously, 20 years is a long time. Looking back, it’s hard to fathom the scope of it. It’s true that I have not updated this blog much since I started freelancing back in 2007, and even less over the past decade. But I still feel it’s an important archive of observations about computer and video game history that generally spans the 1960s-1990s, the era of myself and my father.

In my initial 2005 post, I think I laid out the mission statement for the site when I wrote, “I believe we are in the middle of the most important and exciting transition in human history, where humans fully embrace and integrate computers into their lives, changing the way we live, work, and play forever. So it will be important in the future to be able to look back and see how we got there. And I, in my own small way, want to contribute to that effort.”

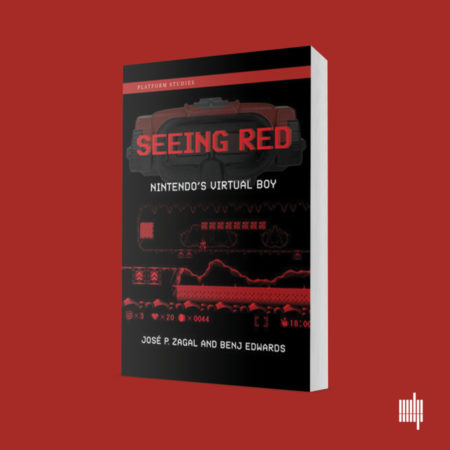

Looking at that statement all these years later, I find that I am very happy with my contribution that happens to span dozens of interviews, thousands of blog posts, hundreds of freelance works, even more posts on sites like How-To Geek and Ars Technica, and one book. All that started here on VC&G.

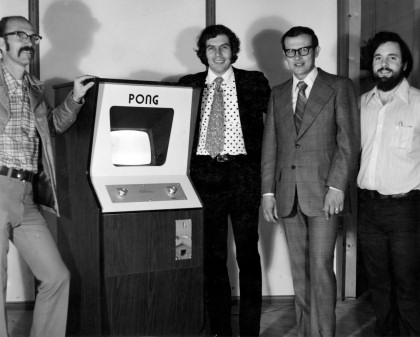

In general, I am not as worried about the preservation of tech history today as I was in 2005. I can’t claim full credit for that achievement, of course, and the best part is that many people who have never read this blog respect tech history now and put great effort into preserving it. So that part is covered, and I think we’ve seen a broad victory for cultural tech preservation. But regarding the “transition” itself — well, there’s a lot more to be said.