The PC is Dead: It’s Time to Bring Back Personal Computing

January 17th, 2025 by Benj EdwardsHow surveillance capitalism and DRM turned home tech from friend to foe.

For a while—in the ’80s, ’90s, and early 2000s—it felt like nerds were making the world a better place. Now, it feels like the most successful tech companies are making it worse.

Internet surveillance, the algorithmic polarization of social media, predatory app stores, and extractive business models have eroded the freedoms the personal computer once promised, effectively ending the PC era for most tech consumers.

The “personal computer” was once a radical idea—a computer an individual could own and control completely. The concept emerged in the early 1970s when microprocessors made it economical and practical for a person to own their very own computer, in contrast to the rise of data processing mainframes in the 1950s and 60s.

At its core, the PC movement was about a kind of tech liberty—–which I’ll define as the freedom to explore new ideas, control your own creative works, and make mistakes without punishment.

The personal computer era bloomed in the late 1970s and continued into the 1980s and 90s. But over the past decade in particular, the Internet and digital rights management (DRM) have been steadily pulling that control away from us and putting it into the hands of huge corporations. We need to take back control of our digital lives and make computing personal again.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not calling the tech industry evil. I’m a huge fan of technology. The industry is full of great people, and this is not a personal attack on anyone. I just think runaway market forces and a handful of poorly-crafted US laws like section 1201 of the DMCA have put all of us onto the wrong track (more on that below).

To some extent, tech companies were always predatory. To some extent, all companies are predatory. It’s a matter of degrees. But I believe there’s a fundamental truth that we’ve charted a deeply unhealthy path ahead with consumer technology at the moment.

Tech critic Ed Zitron calls this phenomenon “The Rot Economy,” where companies are more obsessed with continuous growth than with providing useful products. “Our economy isn’t one that produces things to be used, but things that increase usage,” Zitron wrote in another piece, bringing focus to ideas I’ve been mulling for the past half-decade.

This post started as a 2022 Twitter thread, and I’ve offered to write editorials about my frustrations with increasingly predatory tech business practices since 2020 for my last two employers, but both declined to publish them. I understand why. These are uncomfortable truths to face. But if you love technology like I do, we have to accept what we’re doing wrong if we are going to make it better.

Learning From the Past

While consumer and computer tech today is more powerful than ever before—and in some ways far more convenient—some of the structural ways we used to interface with technology companies were arguably healthier in the past.

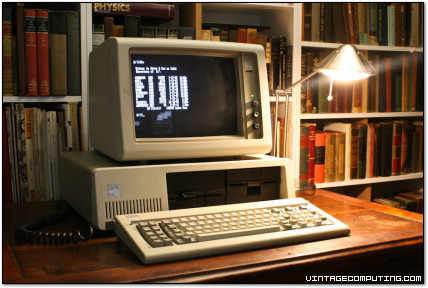

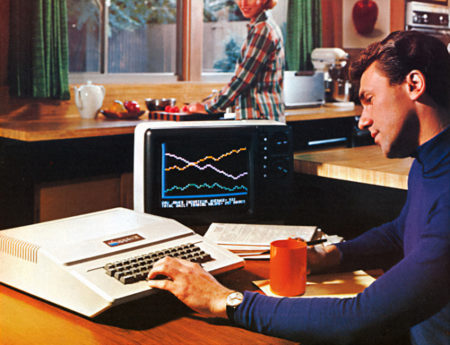

For example, which part of the Apple II was predatory? It promised productivity, education, and entertainment. You could program it yourself, repair or expand it without restriction. No subscriptions, no hardware DRM (though there was software copy protection), no tracking. No need for special tools to repair it either. In fact, Apple openly encouraged experimentation.

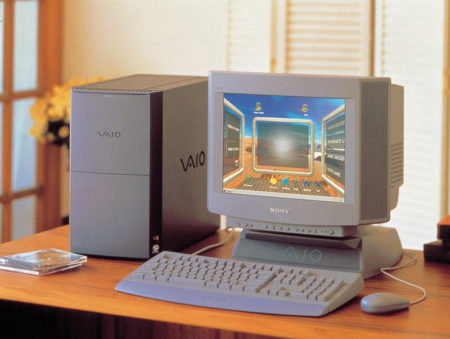

Further, what percentage of your income had to go towards annual software subscriptions on a 20th century Windows PC (like this Sony VAIO)? You bought an application and you owned an indefinite license to use it. If there was an upgrade, you bought that too. And if you liked an older version of the software, you could keep using it without having it vanish in an automatic update.

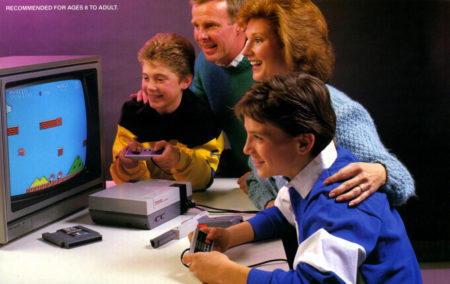

How many Nintendo Entertainment System games sustained themselves with in-app purchases and microtransactions? What more did the console ask of you after you bought a cartridge? Maybe to buy another one later if it was fun?

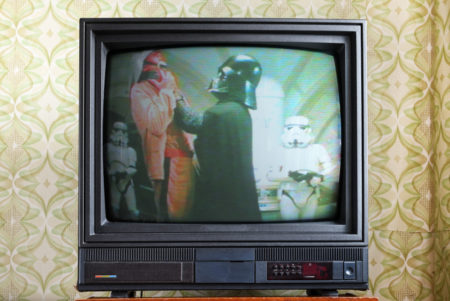

Which part of this TV set kept track of everything you watched and then secretly sold the data to advertisers?

Which part of Windows 95 fed you ads without your consent and kept track of everything you did remotely so Microsoft could keep stats on it? And which part of Solitaire demanded a monthly subscription to play? (And which part attempted to record literally everything you do on your computer?)

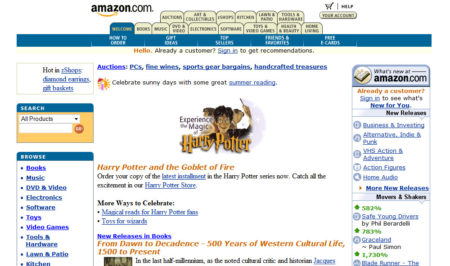

Which part of Amazon.com in 2000 tried to get you to buy millions of no-name counterfeit and dangerous goods propped up by stealth advertising and fake reviews? In its early years, Amazon arguably succeeded through good selection, fair prices on reputable brands, and the wisdom of the crowd through authentic customer reviews.

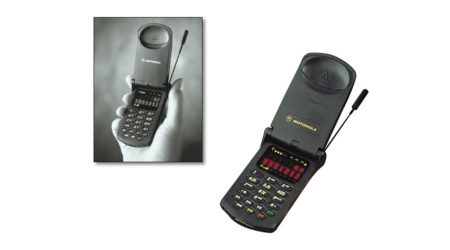

Which part of this Motorola StarTAC cellular phone kept track of your every move and sold the information, behind your back, to private data brokers? And which part included sealed-in batteries that would ruin the entire phone if they went bad?

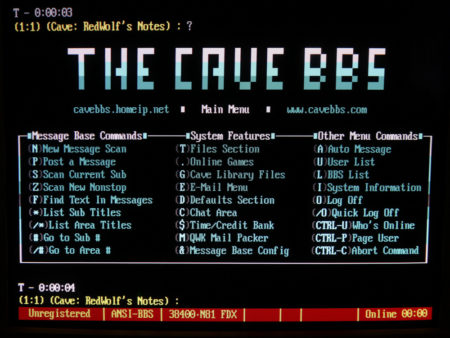

Which part of this BBS used automated algorithms that intentionally fed its users inflammatory and false information to drive engagement for profit? (The users themselves provided the flames.)

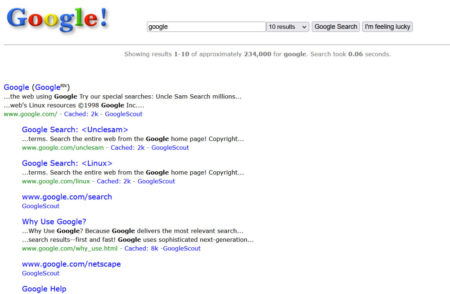

Which part of Google in the 1990s and early 2000s blanketed its results with deceptive ads or made you add “Reddit” to every search to get good results that weren’t overwhelmed by SEO-seeking filler content?

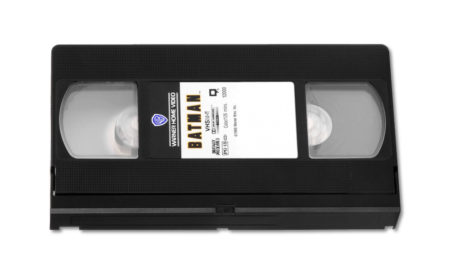

Which part of this VHS tape disappeared or became unplayable if the publisher suddenly decided it didn’t like it anymore—or didn’t want to pay the writers and actors residual fees?

The Extractive Model

Americans have allowed runaway business models, empowered by tech, to subvert privacy and individual liberty on the road to making money. Our default tech business model has become extractive, like part of a strip-mining operation. Consumers—and now creative works (used for training AI)—are treated as a natural resource to be milked and exploited.

The extractive model may end up being self-destructive for the tech industry itself. In the physical world, resource extraction needs limits and regulations to be sustainable. It can be wildly profitable until a resource becomes over-harvested, or the harvesting process corrupts the environment that lets the industry exist in the first place.

There’s also the drive to lock consumers into an ecosystem, powered by DRM. You should buy tech products and get direct value fairly, not unleash a secret vampire to track you, manipulate you, and attempt to extract money from you forever. Just because companies have unlocked this “everything as a service” endless money hack does not mean they should do it.

And there’s another problem. Very soon, we might be threatening the continuity of history itself with technologies that pollute the historical record with AI-generated noise. It sounds dramatic, but that could eventually undermine the shared cultural bonds that hold cultural groups together.

That’s important because history is what makes this type of criticism possible. History is how we know if we’re being abused because we can rely on written records of people who came before (even 15 minutes ago) and make comparisons. If technology takes history away from us, there may be no hope of recovery.

How We Can Reclaim Control

Every generation looks back and says, “Things used to be better,” whether they are accurate or not.

But I’m not suggesting we live in the past. It is possible to learn from history and integrate the best of today’s technology with fair business practices that are more sustainable and healthy for everyone in the long run.

In the short term, we can do things like support open projects like Linux, support non-predatory and open source software, and run apps and store data locally as much as possible. But some bigger structural changes are necessary if we really want to launch the era of Personal Computer 2.0.

I’ve shown this editorial to friends, and some people felt that I did not emphasize the benefits of current technology enough. But I argue that my criticism is less about the actual technology and more about how we use it—and how companies make money from it.

Since I originally wrote my thoughts in a viral Twitter thread in June 2022, others have expanded on these ideas with far more eloquence. Five months after my thread, Cory Doctorow wrote his first post on “enshittification,” a hallmark piece identifying a tendency for online platforms to decay over time.

A common thread between many of the issues hinted at above and in both Doctorow and Zitron’s work has been the rise of the ubiquitous Internet, which has allowed content owners and device makers to keep an eye on (and influence) consumer habits remotely, pulling our strings like puppeteers and putting a drip feed on our wallets.

Additionally, section 1201 of the DMCA made it illegal to circumvent DRM, allowing manufacturers to lock down platforms in a way that challenges the traditional concept of ownership, enables predatory app stores, and threatens our cultural history.

We need comprehensive privacy legislation in the United States that enshrines individual privacy as a fundamental right. We need Right to Repair legislation that puts control of our devices back into our hands—and also DRM reform, especially repealing Section 1201 of the DMCA so we can control the goods we own and historians can preserve our cultural heritage without the need for piracy.

Tech monopolies must be held to account, the outsized influence of some tech billionaires must be held in check, and competition must be allowed to thrive. We may also need to consider the protection of both consumers themselves and human-created works (including our history) as part of a conservation effort before extractive models permanently pollute our shared cultural resources.

The way the political winds are blowing right now in the US, significant legal reform seems unlikely for now. Things may need to get much worse before they get better. But the kind of extractive lock-in we’re seeing with technology is fundamentally incompatible with freedom in my opinion, so something needs to change if we still value the kind of personal liberty the PC once promised—that freedom to explore, create, and make mistakes without surveillance or punishment.

Sure, things will never be perfect in the United States. Profits will always be chased, and there will be collateral damage. And yes, some parts of technology today are better than ever (computing power, screen resolutions, and bandwidth to name a few).

The Internet has brought amazing things, including Wikipedia, The Internet Archive, multiplayer online gaming, VC&G, and work-from-home jobs. But the urge to exploit users to the maximum extent through digital locks and surveillance should be held in check so that we can earnestly and honestly make the tech industry a beacon of optimism once more.

The stakes are higher now than they were in the 1970s. There is no “logging off,” nearly everyone has a smartphone in their pocket, and the digital world increasingly overlaps with every aspect of our lives. That means digital freedom is now equivalent to actual legal and personal freedom, and we must be allowed to control our own destinies.

Whether through purposeful reform or the eventual collapse of digital strip mining, I believe the personal computer will eventually rise again—–along with our chance to reclaim control of our digital lives.

Feedback Update: 01/21/2025

Since publishing this piece, last Friday, I’ve seen a lot of positive feedback for this piece, but also some frustration that I didn’t break down more specific personal, individual solutions to these problems.

As most technically-included people know, we’ve already been enacting those personal solutions for decades. We may store our own data locally on NAS devices instead of the cloud, use open source software, try to preserve privacy with VPNs, etc., but it has not stopped the tide of abuse from the tech industry. And I think that mainstream tech consumers (for example: most of my family members and friends) have no inclination to ever do any of those things.

That’s why I feel like the problem presented here is systemic and needs deep regulatory reform for things to actually get better in the United States. I think a good parallel may be climate change, where putting the onus on the individual to recycle or use fewer resources is misleading, when the biggest environmental abusers are large corporations and industries in aggregate. That needs deep systemic change too.

Also, I think that technical people tend to immediately reach for technical solutions, but I don’t think this is a technical problem. Capitalism, when left lightly regulated, will do what it always does: Pursue the accumulation of capital at all costs, even while damaging society at large. But I am not anti-capitalist: It is a potent tiger with great potential benefits, but it needs to be kept properly in a cage, or it will devour all of us. We should not fall into binary positions. We need balanced regulation that maintains healthy profit-driven competition but keeps capitalism’s worst tendencies in check. Achieving that is admittedly very difficult in these highly polarized times.

So I feel the issues here are ultimately systemic policy problems that need to be fixed with regulation (such as enact national right to repair laws, de-fang the DMCA, implement US national privacy protections, somehow limit the massive seemingly untouchable influence of big tech companies, and probably tax down tech billionaires).

That’s a big ask that feels insurmountable at this moment, but it’s a movement can start now with people who are fed up with our current de facto abusive tech business models. I think eventually we will get there anyway, because the I am not sure the current extractive model is sustainable without encountering massive social unrest within the next decade. The alternative to change, if taken to an extreme, may be the collapse of personal liberty for everyone.

In the meantime, while these lofty goals simmer and take shape, you can also continue to take personal steps to preserve your own tech liberty. Support nonprofits like the EFF that fight for privacy and user rights, strong encryption, open source, use local storage, and so on. I highly encourage it.

Ultimately I hope these thoughts can be a starting point for others to pick up the torch and build off of. I will also be thinking of constructive solutions for a future follow-up.

This is not the end of the conversation—it’s only the beginning. While systemic reform is essential to reclaiming broad personal liberty for everyone in the digital age, the new Personal Computing movement starts with you. Together, we can push for the regulations and systemic accountability that will restore true personal freedom in technology.

January 17th, 2025 at 8:43 pm

A great read! Came here from your BlueSky post. As someone who had access to PCs in the late 80’s onwards the continual “loss of control,” especially in the last decade, has been a constant concern.

I’m sure you’re already aware of it but if not please check out the StopKillingGames movement and it’s attempts to prevent these practices eradicating games by creating laws to prevent it.

January 18th, 2025 at 9:24 am

Thanks, Kaaboose! Glad you enjoyed the piece. I’ll check out the StopKillingGames movement.

January 18th, 2025 at 12:50 pm

What about solutions?

– Use a good, dedicated, firewall

– Use a Pi-hole

– Use DuckDuckGo or equivalent search product

– Use browser add blockers, etc.

– Use DRM free content

– Use a VPN

– Properly configure OS security/privacy settings

– Use an iPhone (privacy/security)

I use Linux but I don’t think it is necessary if one follows the above.

Write an article that outlines solutions.

January 18th, 2025 at 2:51 pm

I could not agree more. I’m on board and ready to start.

Also, great job mentioning Ed Zitron, he one of my current favorites.

January 19th, 2025 at 9:03 am

Thanks for this well-written, well thought out piece. I’ve worked in the software industry for 25+ years, and have watched with dismay as these trends unfold. I do implement some of Andrew Broadfort’s suggestions, but unfortunately, the big tech companies can bank on the fact that such pro-active measures are too much for the average user to implement.

It’s getting worse too. Many people try to opt of big tech’s dark patterns and exploitative terms of service by running their own blogs, personal interest sites and discussion boards. Those are now being almost DDOSed by abusive crawlers and scrapers. There was a lively discussion about this on Hacker News yesterday. See https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=42750420.

I wonder if the AI slop now flooding into major platforms will finally drive users away. And if it does, where will users go? How will they find those personal interest sites and mini communities? How will the site operators keep them running?

January 19th, 2025 at 10:48 am

There was a short period of time from like 2003 to the mid 2010s when the IT business was doing “create more value than you capture” (Tim O’Reilly) and the default setup was pretty good. Before that there was a big win in developing “power user” skills to get your computer to do the right thing.

Now it’s going to be more rewarding to be a power user again… https://blog.zgp.org/return-of-the-power-user/

January 19th, 2025 at 11:38 am

You’re analysis is correct. In reference to the April post one of the advantages of being Gen X is knowing (and remembering) what life was like before tech dystopia took over the mainstream. I ran the same Windows XP machine for about 19 years and when it fiiiinally died in 2020 already knew that (for me) the only way forward was going all in on the Linux/Open Source ecosystem. I’m thankful for the timing as well since, arguably, it’s just been in the last 5 or 6 years that operating systems like: Mint, Ubuntu, Elementary and Zorin are polished enough for normal users.

January 19th, 2025 at 6:53 pm

I have to take issue with Andrew Broadfort’s advice to use an iPhone in the context of this piece. A device with a locked bootloader and poor options for installing software outside of the manufacturer’s app store is in direct opposition to the spirit of making computing personal again.

An unlockable Android device running an open source ROM is closer, though that does come with a learning curve and some pain points, much like running Linux on the desktop.

January 19th, 2025 at 7:12 pm

There actually were self-erasing VHS tapes!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iH4UFUdlmSo

However, they were designed to limit views rather than fulfill the capricious whimsy of backroom contract negotiations. You knew what you were getting up front when you bought one, which is more than we can say for modern streaming services…

January 19th, 2025 at 7:55 pm

This echoes some themes from Carl Sassenrath’s “Back to Personal Computing” (1997)…

https://sassenrath.com/computing.html

January 19th, 2025 at 8:14 pm

I’m building user-centric cartographic software – which would have been a tautology when user outcomes mattered more than surveillance and control.

I have observed that very few people are able to imagine being able to create their own maps, rather than be given an illusion of choice between a few major providers. Some really think they are sticking it to the man with citymapper.

The reality is people have relinquished control. Try and make a statistically significant and graphically excellent map with existing online offerings. The problem is big companies own the web and I doubt they have any intention of making the browser anything but a lite client to their secretive operations.

January 19th, 2025 at 8:31 pm

Love your article and being someone who grew up in the 80s I have always loved computers. The current environment has become so hostile to users that I find myself withdrawing from all social media. I used to love Windows but now the OS has become a junk pile of AI, extracting all your data and spying for the government. I finally left and jumped on a Mac until I got Linux Mint setup on my laptop and desktop.

2025 I see even more surveillance coming and restriction on the media we consume. I wonder if we are all going to go underground and go back to BBS again.

January 20th, 2025 at 12:40 am

All those are valid points. And to help flee from surveillance and closed software I am currently in process to build a website helping people how to build their own “cloud” and using it safely in a friendlier and easier way. We have enough big companies that gathered so much power and money – it must stop now.

If you don’t mind, I’d like to link you from my links section.

Regards,

Chris

January 20th, 2025 at 2:30 am

I enjoyed this read, thank you.

January 20th, 2025 at 7:00 am

I don’t know, I can’t quite put my finger on it – but there’s certainly something missing in the analysis.

I however generally agree and I don’t like big consumer or corporate trends, nor their compromises (more commercial content is available, but it’s not remixable and there’s wonky DRM-shit) for broader appeal to less tech savvy people who only wishes to consume.

Hm, it might be the egalitarian and universalist pitch in the analysis that bothers me. I mean, not everyone is meant for creating or producing things and concepts – that’s fine. It’s just a bother when people forget us.

January 20th, 2025 at 7:22 am

as the Cypherpunk manifesto stated: “We cannot expect governments, corporations, or other large, faceless organizations to grant us privacy out of their beneficence”

and “We must defend our own privacy if we expect to have any”

cypherpunk is the only way to go.

January 20th, 2025 at 8:50 am

If you want an old school web experience, try the Gemini protocol. It is designed to resist many of the privacy eroding features we have unfortunately come to expect in HTTP/S. It’s protocol and document specification are so simple, hobbyist programmers can code up a client and server in a couple of weekends.

=> https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gemini_(protocol)

=> https://geminiprotocol.net/

=> https://gmi.skyjake.fi/lagrange <- most popular browser

January 20th, 2025 at 9:51 am

Wonderful piece. As a developer of open source SW I agree totally with the open source focus, right to repair as it applies to software and also the critical part IMO of owning your own data locally on your machine not in some cloud service you cannot control or manage. Thanks for explaining the issues so well.

January 20th, 2025 at 9:51 am

The homelab movement is still relatively small, but thriving community of people that feel this way. It can be very difficult and frustrating, but the rewards are sweet freedom! It reminds me a lot of the mid-late 90’s when it all felt like new frontier to explore.

Bonus if you get bit by that Data Hoarder bug and get to preserving things that folks take for granted. Great article! Cheers

January 20th, 2025 at 10:25 am

Thought-provoking article, Benj. The reality is too few people even think about their digital rights and privacy, and lack thereof. We blindly agree to user agreements so we can access the products we purchase, or agree to be tracked before we can access content on many websites.

Depending on your age and amount of tech utilized, companies and organizations have been gathering (and purchasing) info on us for years, to use and promote products and services to us semingly out of the blue. “I was just thinking about (insert product). So funny how this ad just popped up,” we often tell ourselves. It’s not coincidental, though.

To an extent, part of ourselves, our interests, our wants, our habits, have become part of the technology we use each day, which shapes future tech to meet individual needs. Tech has also reached a point that free will is being taken away to a degree. Instead of searching for content that might interest us, tech tells us what we would be interested in. It does the thinking for us because it does a good job tracking us. I’ll just state this is very dangerous if you think aboit how it is being used to reshape political opinions and beliefs about certain topics and individuals.

One solution to regain or protect digital privacy is to adopt something similar to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. As a mental health professional, all data we collect of our clients (i.e. progress in treatment, what is said in sessions) is confidential. It cannot be shared or sold, and is only used internally, such as when other providers, who are part of a clients treatment, can read the client’s records to assist the client and the treatment team.

The only reason we break confideitnality is if there is an iminent safety risk in which the client discloses a viable plan and intent to harm themselves and/or others, or are in immediate danger. We tell clients their information is confidential and explain limitations of confidentiality. In order to share data with others, clients need to sign a release of information for each individual or organization data is shared with, which is ususlly only done as part of a client’s treatment to coordinate services.

Comsumers as a whole, should have similar rights. We should be able to discern when amd to whom our data is shared, and for what. User agreements should also be modeled after informed consent forms, which are short documents clients are given that clearly outline what they’re agreeing to and their rights, before they agree and receive services. User agreements are ridiculously long and contain too much legal jargon so comsumers are not really informed aboit what they’re agreeing to in the first place.

Unfortunately, I don’t see things improving anytime soon given the political climate and the unfortunate reality that tech billionaires have aligned themselves with politiicians and are enmeshed in the political system themselves.

Sorry for the long response. I hope it wasn’t too tangential, but there is a lot to be said on this topic.

January 20th, 2025 at 12:36 pm

The comparison with the past really hits home, especially the part about owning and controlling your own software and devices. Do you think we’ll see a larger cultural shift towards self-hosting and open-source tools, or is the convenience of big tech too strong for most people to let go of?

January 20th, 2025 at 12:39 pm

“I’m building user-centric cartographic software –”

What do you think of OpenStreetMaps?

January 20th, 2025 at 11:00 pm

I fully support pushing for open-source tools, Right to Repair, and stronger privacy protections. It’s time to re-prioritize user freedom and make technology personal again.

January 21st, 2025 at 4:28 am

A wonderful read that reflects exactly my thoughts. Thanks for sharing this. I already started a French draft of my thoughts about this topic, but I was wondering if I could translate your article in French, to make it easier (of course with a link to the original).

Thanks again Benj!

January 21st, 2025 at 10:00 am

Yes Arnaud, you may republish it in French.

Anyone who wants to republish this particular article in any language is free to do so. All I ask is a credit and a link back to this piece.

My hope is that this piece can be the start of a conversation and inspire others to build off of it. It’s not the final answer to the problems presented here.

Benj

January 22nd, 2025 at 5:37 am

I’ll just add a minor thought I’ve had about streaming services.

The promise of streaming was that we’d never have to pay the cable bill ever again(kids today don’t know how much we hated the cable company). The reality is we’re paying a cable bill for every channel we watch, and each of these rentseekers is somehow worse than the reviled cable company of old.

January 24th, 2025 at 6:38 am

As I see it, the main problem is laziness.

Yesterday was half wasted as I tried to get my new version of W11 to work properly. It couldn’t detect jpg as a file type and insisted I opened it in Paint, then Photo Printer. Hours of messing around. It re-introduced the user picture on the login yayaya… Hours of searching, registry changes, cmd entries, all to just try and get back to a working OS (I gave up and rolled back).

How many ordinary PC users do you think have ever even used cmd/powershell? I’d say the vast majority don’t even know such a thing exists, let alone have any knowledge of basic commands. They don’t want to know.

Transportation is the same. Vehicles don’t even have carburettors to be adjusted and the majority are pleased with that (until they have to bring their vehicle to an authorised dealer and pay a fortune to have a laptop plugged in to their OBD port).

Every area of tech is now controlled with built-in obsolescence, which was taught as part of engineering back in the 1990’s. It is the model that companies work to since advances in, let’s say “vehicles”, produced an item which was so reliable and simple that it wasn’t wearing out. Not wearing out meant no new ones were going to be sold and the only way to gain profit was in servicing. Cue “end of life” where manufacturers stopped producing the parts required to maintain older models and encourage you to get a newer model.

PC’s are exactly the same. Need a new AGP graphics card for your PC? How about an ISA card?

With the upcoming demise of W10, just how many users are going to get with the programme and buy a new PC? What happens to those millions of perfectly good/functional computers? The public are certainly not going to look at alternative OS’s.

The majority of people I know have never even heard of AliEx yet are happy to purchase the items that are sold on there for a 10x mark-up on Amazon/eBay. They’re not looking for an alternative… back to my opening: Laziness.

January 25th, 2025 at 6:27 am

@Andrew Broadfort, I understand what you are saying, but also it is sad — there is a limit of time and energy you can put (as an individual) against aggressive tech.

Some choices are not made by you at all, not 100% related to the article, but still — post offices are being killed by automatic delivery boxes. Great, they are open 7/24, all you need is code, and here you go, you open the box, and get your package. No wonder post offices don’t grow because people (me including) prefer those automatic ones. But here is the twist. There are new automatic boxes, without any kind of keyboard, you have to operate one with your mobile phone (which you are required to have at this point), with installed, proprietary app (which is mandatory) with paid mobile internet connection (which is also must-have). You don’t like the service? Oh, too late, the package is in the box, and besides, post offices are gone, we killed them. Perfect lock-in.

January 25th, 2025 at 10:20 am

Hello, this is Benj Edwards test-posting a comment using OpenAI’s Operator! What hath god wrought.

January 29th, 2025 at 3:24 am

Why do you blame Capitalism?

If a Free Market still existed, there would be multiple privacy-respecting alternatives available competing for consumers.

There is no competition anymore. In all communications, like social media, telephone, file format standards, etc., there are natural monopolies that prevent this competition from happening.

What we need is to distinguish platforms from regular products, to restore competition.

A platform is any product that gains in value for any given user by the number of users that it has. That amount gained by user addition ought to be taxed away to prevent enclosing of the commons and any consequent rent-extraction (by means of extortion). For example, all app stores.

Platform standards (for example, an OS ABI) should not be protected by copyrights or patents and ought to be well documented to facilitate easy re-implementation by competitors. Companies then ought to compete on implementation of the standard (which is a natural monopoly, as explained already, and ought to belong to all end-users).

Only in this way will we ever be free again.

If platforms tend to become monopolies due to natural network effects, only all end-users ought to control the standards, and the platforms ought to always be open to everyone. This way, the end-user will control the direction of the products that will have to serve the end-users.

Computing became personal and individual during Ronald Reagan’s governance of California (and Silicon Valley) who was the biggest individualist politician in centuries. Then his presidential era grew the market. It is with the end of the presidency of Ronald Reagan and the collapse of the Free Market in the USA that we gradually lose our freedom.

When there was no longer ATARI Computers, Commodore, Digital Research, etc., and Apple was saved by a cash infusion by Microsoft itself (to avoid looking like a monopoly to avoid being broken up as ordered to but repealed later, and to make Internet Explorer a monopoly, part of the deal), only two, three gaming consoles instead of the innumerable consoles that existed in the past.

Do note that all the personal computers of Apple, ATARI, Commodore, and IBM-Compatibles had simple software delivery. You bought shrink-wrapped software or got shareware, and you executed from floppy or installed/extracted on your home computer and ran. No compilation, no complicated package management, no source code.

Yet aside from piracy countermeasures, there were no violations of the user’s rights.

Does Linux, BSD or any other libre or open-source Operating System today use such easy package management with any consistency and popular adoption ?

We are drowning in library and dependency hell on Linux; any solutions offered are either too complex (for example, containers) for non-computerphile expert-users (musicians, for example), or are not adopted, like AppImage that are OK but too few are available, they are too limited, etc.

Why has Linux not copied macOS instead if it cares for end-users and personal computing?

Well, because Linux is a UNIX clone, and UNIX was the enemy of personal computing in the 70s-80s-90s.

Linux may be open-source, but it is not tailored towards individual use. It descends from a time of administrators that controlled expensive systems that you, the user, used sparingly with care under supervision in a University setting (mostly). The admins took care to install all software (and thus were experts), and the interface was a teletype or teletype descendant serial interface, a terminal, that line fed you the output.

That is why Linux is stuck on the server and will remain stuck unless we get a good desktop experience with easy software deployment like macOS or even Windows.

Home computers used TVs like Apple II, full-screen interactive graphics.

Linux or anything like it is not the proper basis for a home computer/personal computer operating system. We would need to adapt Linux like Steve Jobs did with his UNIX-based macOS, or base our home computing on something else. Something like a heavily reworked AROS or ReactOS. Both presently have zero hope of ever becoming viable competitors. No funding, slow development, stuck in 32-bits (AROS does not even have memory protection, making it prone to corruption with the modern badly written software with bad memory management that exists today, try it).

There are still some commercial OSs like AmigaOS 4.1 (limited memory protection, stuck in ppc) and ArcaOS that qualify as somewhat adequate, mostly offline personal computing OSs I guess, but for how long will they survive stuck in 32-bits with limited (often expensive and weak hardware) and, let’s face it, with dwindling software support?

Let alone that proprietary OSs no mater how well-intentioned, are opaque to full security checks.

Unfortunately, it is evident that the consumer is mostly (almost exclusively) interested in communications with their devices, and this is why they have adopted huge PCs, replacing smartphones (at those sizes we used to call them tablets). All smartphones are almost exclusively consumer devices, except for networking and creating relationships (through heavily controlled apps). Is there any wonder we live in a TikTok, YouTube world where most idly watch, wasting their time ?

The PC is truly no more. Maybe we, the actual PC users, could pull some money together and adopt or make a new PC platform based on open standards. Just to save ourselves. But general interest is dispersed, special interest is focused, so it will never happen.

February 6th, 2025 at 3:39 pm

Perhaps a good asset with which to expand this article, see below.

https://wiki.futo.org/wiki/Introduction_to_a_Self_Managed_Life:_a_13_hour_%26_28_minute_presentation_by_FUTO_software

February 12th, 2025 at 7:02 am

@Hanu8

“Linux is a UNIX clone”

well, such a long text with so many insanities.

ever heard of GNU/Linux with a N like Not ? not a decorative word.

“Does Linux, BSD or any other libre or open-source Operating System today use such easy package management with any consistency and popular adoption ?”

any phone ? any fedora based or debian based system ? you name it.

“Why has Linux not copied macOS instead” well, because MacOS copied BSD to begin with !

and that’s a start.