The PC is Dead: It’s Time to Bring Back Personal Computing

Friday, January 17th, 2025How surveillance capitalism and DRM turned home tech from friend to foe.

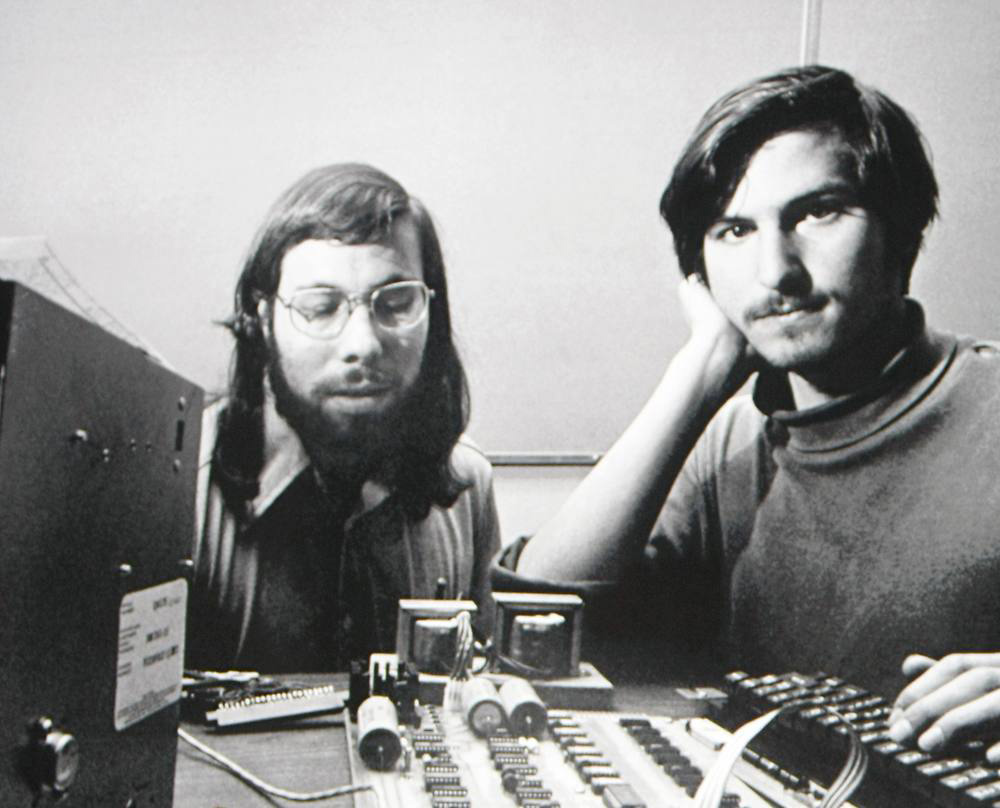

For a while—in the ’80s, ’90s, and early 2000s—it felt like nerds were making the world a better place. Now, it feels like the most successful tech companies are making it worse.

Internet surveillance, the algorithmic polarization of social media, predatory app stores, and extractive business models have eroded the freedoms the personal computer once promised, effectively ending the PC era for most tech consumers.

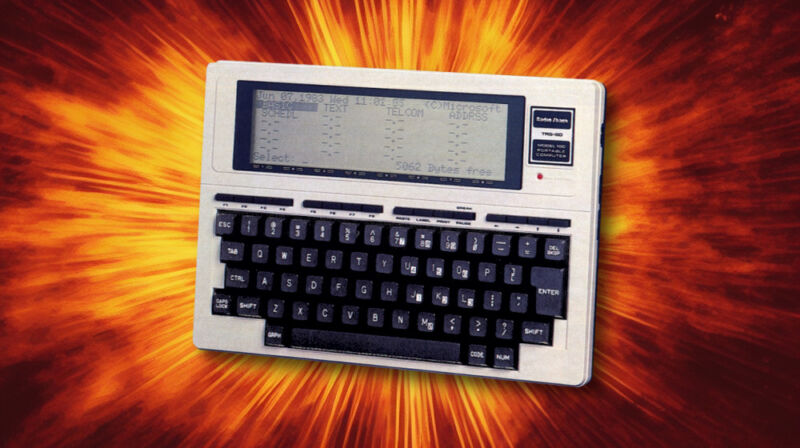

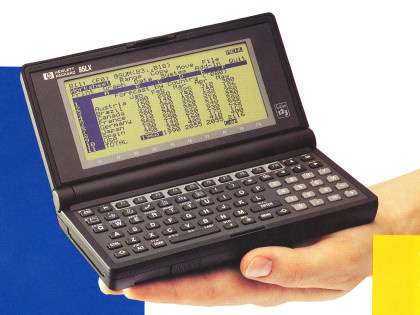

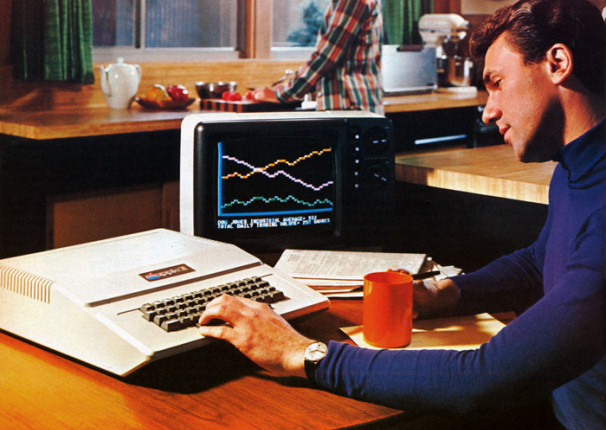

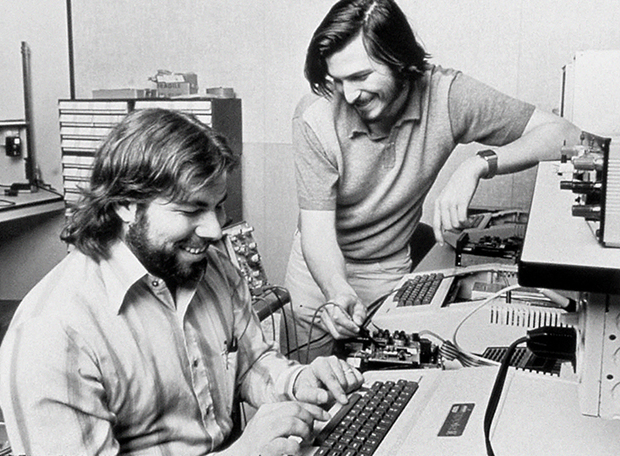

The “personal computer” was once a radical idea—a computer an individual could own and control completely. The concept emerged in the early 1970s when microprocessors made it economical and practical for a person to own their very own computer, in contrast to the rise of data processing mainframes in the 1950s and 60s.

At its core, the PC movement was about a kind of tech liberty—–which I’ll define as the freedom to explore new ideas, control your own creative works, and make mistakes without punishment.

The personal computer era bloomed in the late 1970s and continued into the 1980s and 90s. But over the past decade in particular, the Internet and digital rights management (DRM) have been steadily pulling that control away from us and putting it into the hands of huge corporations. We need to take back control of our digital lives and make computing personal again.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not calling the tech industry evil. I’m a huge fan of technology. The industry is full of great people, and this is not a personal attack on anyone. I just think runaway market forces and a handful of poorly-crafted US laws like section 1201 of the DMCA have put all of us onto the wrong track (more on that below).

To some extent, tech companies were always predatory. To some extent, all companies are predatory. It’s a matter of degrees. But I believe there’s a fundamental truth that we’ve charted a deeply unhealthy path ahead with consumer technology at the moment.

Tech critic Ed Zitron calls this phenomenon “The Rot Economy,” where companies are more obsessed with continuous growth than with providing useful products. “Our economy isn’t one that produces things to be used, but things that increase usage,” Zitron wrote in another piece, bringing focus to ideas I’ve been mulling for the past half-decade.

This post started as a 2022 Twitter thread, and I’ve offered to write editorials about my frustrations with increasingly predatory tech business practices since 2020 for my last two employers, but both declined to publish them. I understand why. These are uncomfortable truths to face. But if you love technology like I do, we have to accept what we’re doing wrong if we are going to make it better.

[ Continue reading The PC is Dead: It’s Time to Bring Back Personal Computing » ]