From the 1990s until very recently, the press has been generally unkind to the achievements of the first IBM PC. Due to the PC platform’s utter dominance of the personal computer market, popular accounts of personal computer history commonly paint IBM as the slow, lumbering, clueless enemy while cheering on spunky underdogs like Apple. I’m not even going to cite specific examples: Google “computer history.” Read. You will see it.

But that perspective is not fair at all. IBM truly pulled off something smart, savvy, and remarkable in designing the IBM PC 5150 (and the machines that followed it, into the PS/2 era). With the 5150, a team of 12 people took the machine from concept to shipping product in less than a year. And yet many focus on how IBM supposedly lost its way.

Much ballyhoo has been made, for example, about how IBM lost its grip on the PC’s direction as clones flooded the market. From a different perspective, that runaway-freight-train-of-a-platform is a success story for IBM.

Much ballyhoo has been made, for example, about how IBM lost its grip on the PC’s direction as clones flooded the market. From a different perspective, that runaway-freight-train-of-a-platform is a success story for IBM.

While Big Blue lost market share to clone manufacturers, you have to keep in mind that IBM’s percentage shrank as the market size exploded. IBM fostered a rich PC standard that it kept reaping until it sold its PC division to Lenovo in 2004. IBM may not have kept steering the ship, but they sure made a lot of money in the cargo hold.

And if you think IBM’s influence on the PC standard ended in the early 1980s, think again. Real history is not so cut-and-dry. The PS/2 era (which dawned in 1987) gave us stalwarts like the PS/2 mouse/keyboard ports and, ah yes, that minor display technology called VGA. You can also thank the 1990s ThinkPad line for its part in streamlining the modern laptop.

The popular narrative of IBM vs. Apple in the 1980s, with its strong contrasts of Good vs. Evil and Hero vs. Villain was largely a creation of Apple’s marketing department. The image of Apple’s David verses IBM’s Goliath got repeated so many times that the press started using the supposed rivalry as the basis of dramatic stories. Humans need narratives to make sense of history, and writers have forced the PC market story into that archetypal mold.

Sure, IBM and Apple competed for dollars — and they may have even done it vigorously — but business is business. It’s not swashbuckling. The first thing you learn when actually studying computer history (i.e. interviewing folks) is that just about no one involved in creating these products thinks they were doing something so incredibly amazing that it should be turned into a movie. They were just doing their jobs, developing good products, and trying to make money like everyone else. When the project was over, they moved on to other things. That story is incredibly boring if you don’t dramatize it.

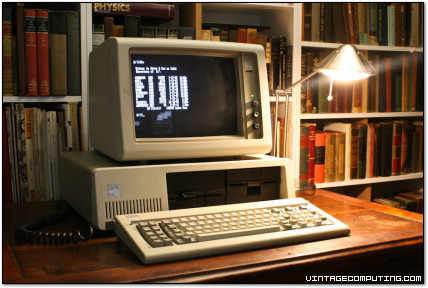

By using the IBM PC for a week for a recent article, I learned firsthand that the original PC really was an amazing machine for its time. It wasn’t just a generic box that happened to have an IBM logo on it, as some people argue. Sure, it didn’t have flashy graphics or a GUI, but it was solid, reliable, well-designed, and it was definitely the most qualified personal computer for getting work done in 1981. There is a reason it became a standard, after all — everyone imitated it, and they imitated it because it was amazing.

Much ballyhoo has been made, for example, about how IBM lost its grip on the PC’s direction as clones flooded the market. From a different perspective, that runaway-freight-train-of-a-platform is a success story for IBM.

Much ballyhoo has been made, for example, about how IBM lost its grip on the PC’s direction as clones flooded the market. From a different perspective, that runaway-freight-train-of-a-platform is a success story for IBM.