In Memoriam: Samuel Frederick Dabney, Jr. (1937-2018),

In Memoriam: Samuel Frederick Dabney, Jr. (1937-2018),

co-founder of Syzygy and Atari

Samuel Frederick (“Ted”) Dabney, Jr., who co-founded Atari with Nolan Bushnell in 1972, died of esophageal cancer just three days ago. He was 81 years old.

I was not close with Ted, but I did interview him at length for articles about Computer Space and Pong back in 2011 and 2012. During our conversations, he was candid, detailed, kind, and very helpful. During my conversations with him, a lot of the details of early Atari history you can now read online were coming out of him for the first time, so he was a vital source of fresh information on that subject.

Ted did critical work as a partner of Nolan Bushnell in the early 1970s. He served as a creative sounding board for Nolan’s ambitious ideas and also as a key implementer of some of them.

Ted met Nolan around 1969 while working at Ampex, where they were office mates. They shared big dreams and secret sessions of the board game go while in the office, and in off-hours, they hung out and scouted locations for a new restaurant idea Bushnell had that involved talking barrels.

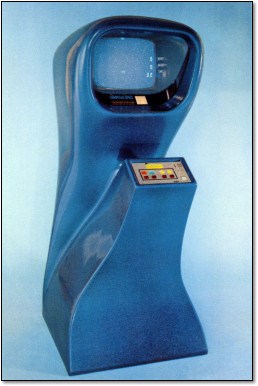

With Nolan at Syzygy Engineering, Dabney created the video control circuitry used in Computer Space, built the prototype cabinet for that game, designed its sound circuit, and more. On Pong, Dabney built the prototype cabinet and gave feedback to game designer Allan Alcorn. He also provided ideas for Atari’s third game, Space Race, before he left Atari in 1973.

There is some confusion about the reason Dabney left Atari. Dabney told me that Nolan forced him out. Bushnell commonly cites poor work performance as the reason Dabney left. Absent some documentary evidence, the real answer will always be one of those fuzzy historical points left to interpretation. What we do know for sure is that the two founders were no longer getting along.

There is some confusion about the reason Dabney left Atari. Dabney told me that Nolan forced him out. Bushnell commonly cites poor work performance as the reason Dabney left. Absent some documentary evidence, the real answer will always be one of those fuzzy historical points left to interpretation. What we do know for sure is that the two founders were no longer getting along.

(By the way, I have recently read some reports about Dabney that say he left Atari because he was angry that Nolan patented his motion control circuitry without including him on the patent. This is plainly false. Dabney did not even know that Nolan’s motion control patent existed until I informed him about it in a 2011 interview.)

A lot of the key info I gleaned from Dabney can be found in my 2011 piece on Computer Space, which is a primary source for some of the secondhand knowledge you’ll read about Dabney and Atari’s early days on the web. Some day I need to publish my full interview with Dabney on Pong, because it is very insightful.

It’s also worth noting that Dabney remained friends with Nolan throughout the 1970s despite the Atari business acrimony. They were never truly close like they were circa 1969-1972, but they still kept in touch, shared a hot tub or two, and Dabney created a trivia game for Nolan’s Pizza Time chain in the early 1980s.

I will miss talking to Ted. He was laid-back, easy going, and straightforward. He had so much skill and experience from his days before Atari, and I need to write about that some time. I had hoped to interview him again at some point, but life delayed those plans. May he rest in peace.

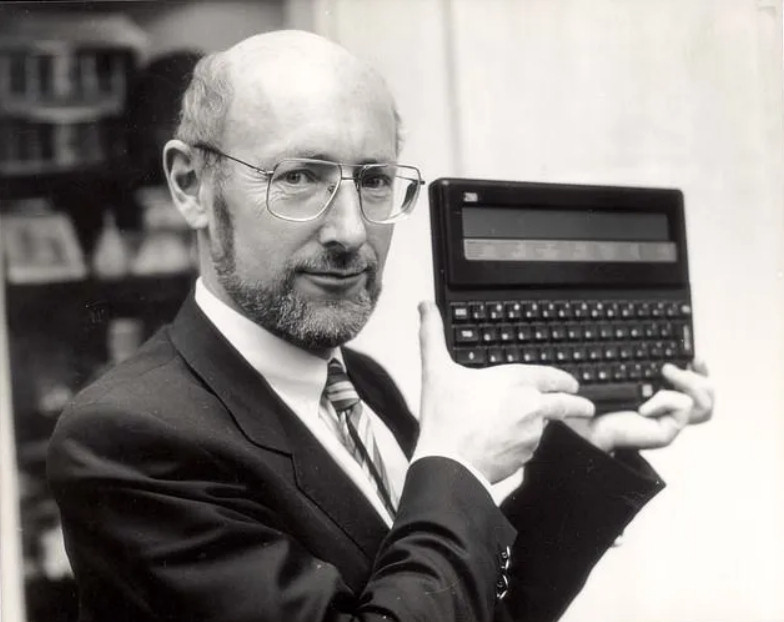

In Memoriam: Clive Marles Sinclair (1940-2021)

In Memoriam: Clive Marles Sinclair (1940-2021)

There is some confusion about the reason Dabney left Atari. Dabney told me that Nolan forced him out. Bushnell commonly cites poor work performance as the reason Dabney left. Absent some documentary evidence, the real answer will always be one of those fuzzy historical points left to interpretation. What we do know for sure is that the two founders were no longer getting along.

There is some confusion about the reason Dabney left Atari. Dabney told me that Nolan forced him out. Bushnell commonly cites poor work performance as the reason Dabney left. Absent some documentary evidence, the real answer will always be one of those fuzzy historical points left to interpretation. What we do know for sure is that the two founders were no longer getting along.

[The following news comes to us via video game historian Mary Goldberg, who has allowed VC&G to republish his

[The following news comes to us via video game historian Mary Goldberg, who has allowed VC&G to republish his